Eyes wide shut

In building a figure from clay we might start from the inside—the kernel of vital organs perhaps—and work our way outwards. This process would mean that each substrate, each increasing layer, would be felt into being by the fingers. Classical sculpture (or drawing, or painting) insists that any figure is first and foremost a volume that is supported by an inner structure; a musculature that defines the form of the outer surface that the eye perceives. Understanding the ‘inner’ layer thus allows the correct depiction of the ‘outer’. This is why artists of the Renaissance undertook to record the anatomy of the human body as a surgeon might; by peeling back subsequent layers and analysing the contingency of each part upon the whole.

But this kind of analytical approach only takes us so far. You might argue that even depicting something exactly as it appears to the eye is a gross distortion of how things really are, or at least how things are really perceived. So what if we followed a similar process, but one where a kind of visual feeling took precedent over analytical description? Start from the centre and work outwards again, but this time your eyes are closed and only touch guides the unwinding of material into form. The figure (or drawing, or painting) is only completed when it feels right rather than when it looks right. Limbs might distort, the geometry of space might become skewed, faces generalise, features only partially form. But at one level what we are left with might be a closer approximation of what we set out to achieve.

‘The painter recaptures and converts into visible objects what would, without him, remain closed up in the separate life of each consciousness.’

This is a quote from Maurice Merleau-Ponty writing (in 1945) on Cezanne. In the piece he tries to describe what he saw as Cezanne’s ‘doubt’—that gnawing feeling of failure, or sense of an as-yet unattained ideal which pushed him ever beyond the immediate work at hand. You might argue that Cezanne was a painter who always had his eyes wide open, that he tried to record faithfully what the eye percieved. But in doing this he moved past how the world logically appeared, attempting instead a synthesis of seeing and feeling which embedded him in his subject. Merleau-Ponty quotes him as saying: ‘The landscape thinks itself in me and I am its consciousness’.

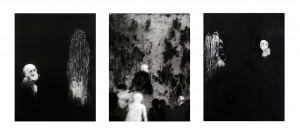

Two current exhibtions set me thinking in this direction: Naomi Eller’s ceramic works at C3 and Brent Harris’s new works at Tolarno. Both artists seem to want to achieve a synthesis between seeing and feeling, to unwind their ‘figures’ from their material ground as though discovering them for the first time. Part of me wants to call this tendency ‘re-classicism’, because in it we recognise something not only fundamental to the creative process, but also a striving to find archetypal forms that underwrite all things. Unsurprisingly both artists make reference to grand Biblical drama. For Eller, Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden provide a meta-narrative which suggests all human struggle, big and small. For Harris it is the Stations of the Cross (and in this series the Fall in particular) which call him to ponder mortality. ‘What happens next’, he seems to be saying, ‘can’t be described, but it can be felt’. If this sounds bleak it’s not. Humour and wonder animate each exhibition. In both, the act of uncovering inner worlds is revealed as one of necessary lightness.

Naomi Eller, Nothing is set in stone, c3 contemporary art space, Melbourne, 21 November – 9 December 2012.

Brent Harris, The Fall, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 21 November – 15 December 2012.