Bright light wakes you early in the tropics, which may reduce anxiety

I escaped a tropical downpour into Hito Steyerl’s Too Much World. The rain came straight down like a wide curtain, heavy and loud. Inside, the overriding mood was Scepticism Inc., a meta-melange of corporate training video, hotel room cable TV, real estate fly-through, political message, financial collapse, weather report, biography and probably even more than this.

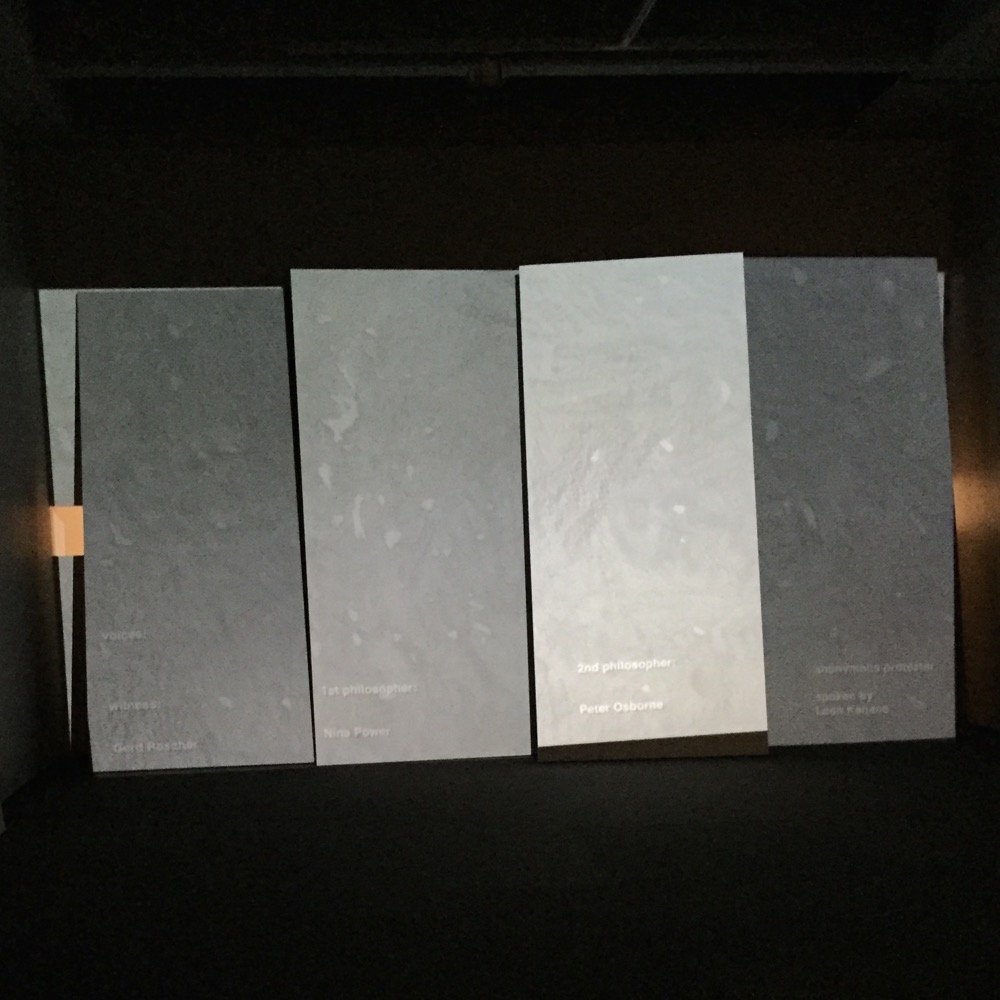

Until the last room, where I sat in a grey-walled space, watching conservators picking and scratching at a wall in a room in a Frankfurt university, in search of the myth or reality of Adorno’s Grey. Their slow, white-coated labour of incremental excavation half a world away was projected onto a screen split into four vertical boards propped against the wall, as if ready for removal at any time. A provisional idea expressed in material form.

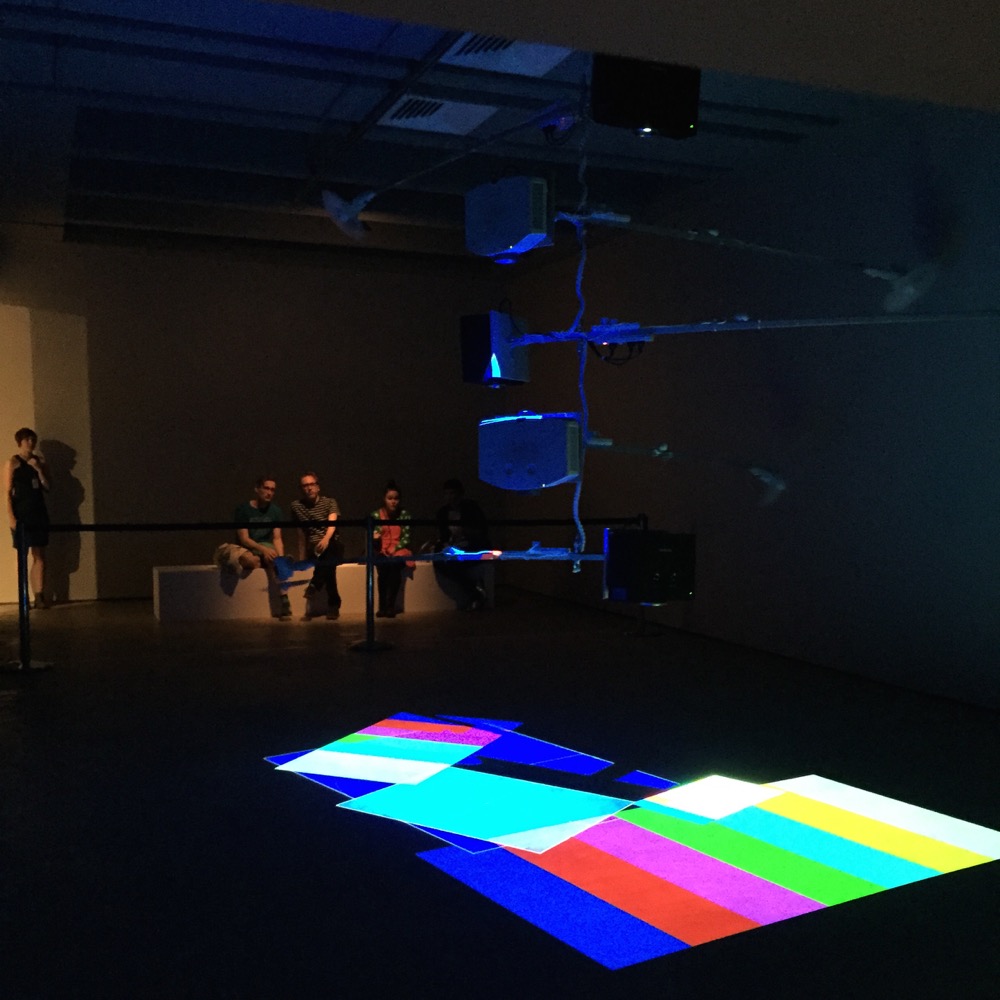

A few weeks later, Ross Manning’s mechanical mobile, Memory Matrix and Antiquity (for synchronized multichannel video) 2015 reached down into the same gallery space from the ceiling, projecting colour calibration screens on the floor from decommissioned projectors. These slowly colliding and intersecting readymade test-patterns of light were without subject matter, beyond themselves.

Melbourne in late autumn was all of its clichés: crisp, cool and dark and full of everything. In the final room of Kaleidoscopic Turn at NGVA, the magnetic video tape floating between two whirring fans in Zilvinas Kempinas’s Double O 2008 drew a hovering frame around Elizabeth Newman’s Untitled 2013 on an adjacent wall. Newman’s minimal work featured a section of slumped and sagging fabric – the result of a simple, three-sided, rectangular cut – which seemed to resist the tenuous optimism of this constantly suspended drawing in space. The gesture delivered a material scepticism, quietly yet insistently spoken.

Hito Steyerl, Too Much World, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 13 December 2014 – 22 March 2015.

Imaginary Accord (Agency, Vernon Ah Kee, Gerry Bibby with Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley, Zach Blas, Ruth Buchanan, Céline Condorelli, Peter Cripps, Sean Dockray, Goldin+Senneby, Raqs Media Collective, Ross Manning, Marysia Lewandowska and Hito Steyerl), Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 11 April – 11 July 2015.

The Kaleidoscopic Turn, National Gallery of Victoria (Australia), Melbourne, 20 March – 23 August 2015.