Something something video-film-paint something (1)

Steve McQueen crossed over in 2008 with Hunger. Gillian Wearing did it in 2010 with her doco/art film Self made, which got neither a major release or a spot in a film festival in Melbourne. On 17 March, at LongPlay in North Fitzroy, Doc(c)o Club returned with a screening of Wearing’s film.

A couple of friends-slash-film-making-colleagues have recently started this film club. Modeled on the reading-group-cum-book-club phenomenon, Kim Munro and Amanda Kerley began Doc(c)o Club with the idea of screening seminal, rare and innovative films that could generate discussion and dialogue. While Doc(c)o Club centres around screening and discussion, Amanda and Kim’s other project, Camera Buff Movie Makers, brings together makers interested in the production of short, essayistic films that question the limitations of documentary making. With funding for documentary film-making becoming harder to get, these projects have provided a way for Amanda and Kim to focus attention and help grow divergent ways of thinking about and telling non-fiction stories.

Amanda and Kim have both engaged in documentary practice. Kim began her foray into the field with the short musical documentary, The rise of Leatherman (2008), following this with Nerve (2011), a made-for-television (in particular the ABC) documentary about the London-based Australian artist, Paul Knight, and his project to find two strangers interested in having sex upon meeting. Together, Amanda and Kim have worked on the short campaign documentary Save the Hope Street bus (Keep our hope alive), made last year following State Government funding cuts which saw the axing of the shortest bus route in Melbourne. The ‘economically irrational’ cuts to the service meant some 150 elderly citizens could no longer be self-sufficient.

Gillian Wearing’s Self made is a cross-over film. By utilizing processes and approaches not unlike her previous works, Wearing made a documentary film that not only traverses a kind of self-help, cathartic-reality TV genre but also a film that, in the end, tends to the dramatic theatrical. Wearing’s doco becomes drama as she weaves together scenarios determined by the film’s own participants and the workshops they have participated in with Sam Rumbelow, a method acting teacher. Scenarios involve a man who has planned his own death and identifies with Mussolini as his on-screen alter ego, a depressed and repressed middle-aged woman who becomes the heroine of a 1940s love story (this reminded me somewhat of Claude Chabrol’s 1970 film Le boucher), and the complicated relationship between a daughter and father, which is replayed via the restaging of Shakespeare’s King Lear. The process of fictionizing self-emanated facts highlights the difficulty of representation—in particular, Wearing’s participants’ complex relationships with themselves and the world.

The participants’ privilege of being able to cathartically engage with their past or present internal conflicts and then reshape that conflict via method acting reminded me of Salvoj Zizek’s 2011 article ‘Shoplifters of the world unite‘, published in the London Review of Books. The text examines the sloganless actions of the London rioters reacting to the shooting of Mark Duggan and their relationship to the European debt crisis through Zizek’s typical Marxist-Hegelian lens—those outside organized social space express discontent through ‘irrational’ outbursts of destructive violence. The rioters’ unspeakable and unrepresentable conflict with the present eventuated in several days of violence and looting; this was a space between rational and irrational, the representable and the unrepresentable, tentative and potentially volatile.

Unrepresentable.

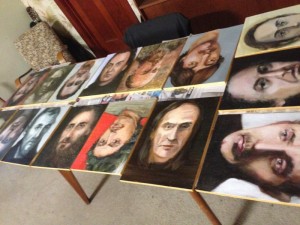

If Wearing’s film can be considered a fictional cinematic portrait of the lives of seven Londoners, I see a parallel with Colleen Ahern’s exhibition Cortez the Killer at Neon Parc this month (previously written about by Hannah Mathews for Stamm). This two-year project has seen the production of more than thirty portraits of a man based on the Neil Young song of the same name, a man Colleen can only imagine. The song references Hernán Cortez, a spanish conquistador who conquered Mexico for Spain in the sixteenth century. The song utilizes a historical narrative and then shifts to what seems like a personal first-person narrative. Colleen has painted the image of this man she cannot see and of whom there is no photographic portrait in existence.

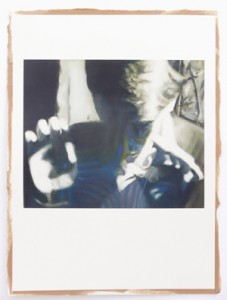

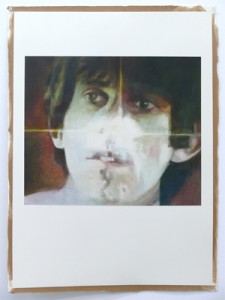

Oil paint can be a slippery, manipulative medium. Sometimes the portrait is a collaged mash-up of faces, another is clearly a painting of someone (whom I am privileged enough to know is Colleen’s daughter) masked with a taped-on moustache and goatee. In the exhibition, we are presented with thirty questions of what a portrait is, what it can and what it can’t be, whether finely glazed and reminiscent of a Velásquez or loosely painted, facial features rendered awkward. I can’t help but think of the Shroud of Turin, or Robin Williams’s character Harry in Woody Allen’s Deconstructing Harry, a man who literally slips out of focus: portraits, pictures and leaps of faith.

In the end, through these works Colleen forces us to make our own assumptions as to who is being depicted and we name them accordingly: the Dave Grohl one, the Alex Vivian one, the Tony Abbott one. What we are left with, perhaps, is the melancholic loss embedded within an endless project. Painting a portrait is difficult at the best of times, but painting the portrait of someone whom one has to imagine, building the face, the structure, the tonality, the touch, is surely near impossible. Colleen gives us thirty paintings about the impossibility of portraiture and representation and the challenge of historical memorialization. Her serialized, fictional portrait of one person becomes a collection of individual portraits of a faceless many.

Note: Kim and Colleen are both very good friends of the writer. Gillian is not.

Colleen Ahern, Cortez the Killer, Neon Parc, Melbourne, 13 March – 6 April 2013.

(1) Something something video something was an exhibition curated by Blair Trethowan and Jarrod Rawlins and presented at Artspace, Sydney, in 2003 and Uplands Gallery, Melbourne, in 2002.