Chua Mia Tee’s Singapore

Singaporean artist Chua Mia Tee’s Epic poem of Malaya (1955) is a history painting of the sort we rarely see anymore—so many aspirations and doubts in the same frame. The image is of students sitting on the ground outside, under a tropical sky, listening and watching a young man speak—a teacher perhaps. It’s a scene that at its surface feels very contemporary. There is a currency today of artists imagining everyday group scenes—in a classroom or kitchen or at a tea party where people interact or just coexist —to describe or interrogate or enact what we share between us. In the context of 1955 the proposition of these students was the design of a state and the possibility of building nations. Or at least Chua Mia Tee was thinking through these propositions with this painting.

What’s unusual in Chua’s work is that there is complexity in the relations displayed between the students listening. There may be shared aspirations but these are not anxiety-free or uniform. There are different reactions and Chua is anticipating these differences collectively. The faces are not evenly focused; it’s a classroom after all. The fly on the man’s shoulder in the foreground anticipates another unmanageable spirit inconsistent with civic schemes. (On the same arm there is also what looks like an inoculation scar.) These qualities subtly distinguish the painting from more recent examples.

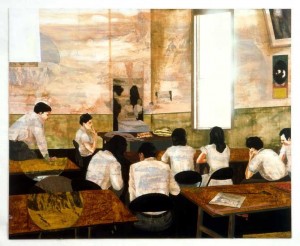

National language class (1959), Chua’s second work in the exhibition A changed world, could almost be a Mamma Andersson painting. The work describes an idea or proposal at a point that predated its actual adoption. National language class is painted ten to fifteen years before a new Singapore adopted two foreign languages as national languages although it wasn’t to be Malay by then, but Mandarin and English. Chua’s painting propagated the view that a new state needed room for the future and so too it needed the strength to make that room and change and so sometimes actively discard certain vernaculars and popular ways.

Equivalent contemporary pictures like, say, Mamma Andersson’s (with titles such as Ramble on or We are much closer than we ever thought), or Helen Johnson’s, with realist titles like History problem, are perhaps by contrast calculated to underwhelm slightly. Contemporary group pictures can resort to a kind of melancholic ‘the way “we” are’. As often there can be a backdrop of inaction, or boredom, or worse, a kind of fateful positivity which just makes me cringe. Chua Mia Tee’s group interplay is more demanding and comes from an environment that obviously was too. Among the deep aspiration there is still a level of uncertainty or irritation that is potentially dangerous and inciting—it’s an image of survival with a face and pressure.

A changed world: Singapore art 1950s—1970s, National Museum of Singapore, 25 October 2013 to 16 March 2014.