I’ve always felt that Justin Trendall’s unique state screenprints attempt to map the nature of memory; the acrobatic things it sometimes does, the mistakes it makes in the pursuit of narrative logic, that kind of thing.

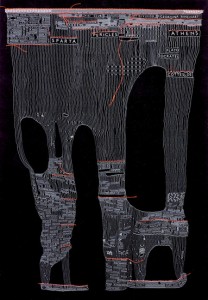

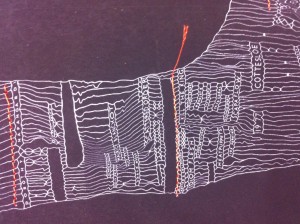

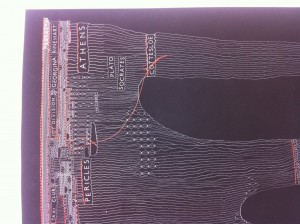

He’s been making the prints for some years now. A handful of new versions are currently on display at Kalimanrawlins. Lists of names—often radically unrelated—embed in finely woven nets. There are often holes. There are also strange stoppages: bottlenecks that funnel one passage of the composition into another.

It might be me but it appears as if, over time, Trendall’s nets have become more complicated and difficult to decipher. He’s not particularly old, but I can’t help feeling that this increased complexity is somehow a graphic rendering of time passed. Existing memories remain the same when in isolation, but surely they change when jammed together with new ones; sense must be made through ever more random throws of the dice. It follows that even as connections become more diffuse and harder to explain, the pattern they trace becomes more complex, more compelling.

History is difficult. The old adage goes that it’s written by the victors. It’s equally true that it’s written by either side of whatever political divide (‘left’ or ‘right’ in Australia) holds sway. New versions only take us so far before they are pulled under by the weight of competing ideologies.

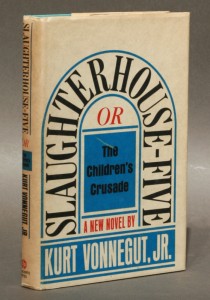

I’m not sure what this means for the kinds of personal histories individuals construct, but one thing that seems relevant here is something that has stuck with me from a teenage infatuation for Kurt Vonnegut’s books. It’s the way he described plotting his famous novel Slaughterhouse 5. He pinned a large piece of butcher’s paper to his study wall and assigned each character a different coloured pencil and then proceeded to draw horizontal lines across the paper. When they reached the bombing of Dresden, which is the novel’s penultimate event, they descended into a scribble from which only a handful emerged.

This is a simple graphic rendering of the novel’s plot. Maybe it’s far too stripped back to tell us anything much at all. But at one level that’s the only truth of things. From this perspective all lives might look something like Trendall’s prints: logic boards that have been superseded, reworked, and relaunched more effective (or defective) than ever. You make your own sense of them, that’s the point.

Justin Trendall, Out one spectre, Kalimanrawlins, Melbourne, 19 October – 9 November 2013.