(Mis)communication rules

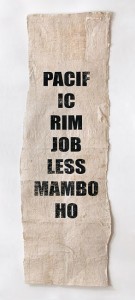

Wikipedia tells us that Creole is a language ‘developed from the mixing of parent languages’. Like Pidgin—a necessary precursor to Creole—it is brought about through the coming together of previously incomprehensible differences. Europe’s colonial expansion brought many creoles into being by way of trade routes, colonial domination and the traumatic displacements of the slave trade. Here, old languages were bastardised to become new. The spread of cultures across the Pacific also necessitated languages of exchange. In northern Australia, the cattle industry, hot on the heels of European invasion, prompted a ‘Kriol’—a mix of Aboriginal languages, English and Chinese—which is still spoken today. At one level the development of such languages displays the need for a common ground on which social, cultural or economic transactions might be negotiated.

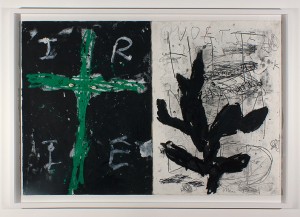

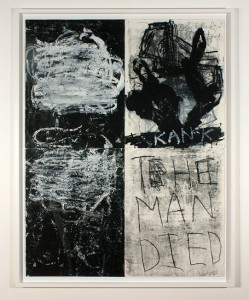

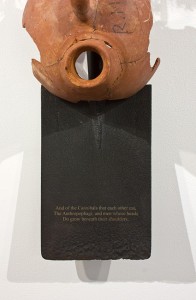

It’s worth considering what this space is. For example, in creating a way by which relative values can be brought into play, are cultural differences transcended? Or, in carefully plotting a space of exchange by the limitations of language, are differences beyond this space consciously maintained? In the works of Sydney-based visual artist Newell Harry we might observe that layers of difference do not necessarily settle into a coherent whole. This disjuncture points towards miscommunication. It echoes the space between languages, a gap where the necessity to communicate prompts new forms which may or may not be adequate for the task.

Newell Harry, Blue pango: musings & other anecdotes, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, 26 July – 18 August 2012.