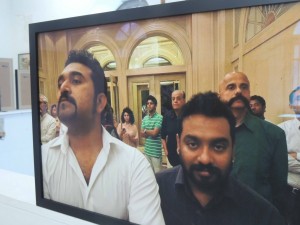

Atul Dodiya’s Kochi–Muziris Biennale installation in a disused laboratory comprised upwards of 200 framed photo-portraits standing on half-size partitions and benches, and hanging on walls. Snapshots taken with a digital camera showed mainly artists and other participants in the Indian art scene, all the individuals in ones and twos and threes, interspersed with the odd art-historical figure and a few David Attenborough-style wildlife pictures.

As a giant, glorious collective portrait of a community, Celebration in the laboratory was multidimensional but reminiscent too of all those many earlier group portraits of artists. Dodiya’s installation was hugely inclusive and at a point intimate, but struck me as capturing a pathos now bypassed elsewhere. The Indian scene (this scene described by Dodiya) is I guess roughly an equivalent size to the Melbourne scene, all up, but I couldn’t think of such a project being conceived, let alone staged, in Australia.

Celebration in the laboratory communicated something of the purpose and confidence of the Indian contemporary art scene in its current state. People seem to know one another. Infrastructure, like the architecture, is generally very low to the ground. Cross-generational networks are visible. Shared knowledge and enthusiasms between artists matter.

International art events are like international airports. If you have one, people come. If you don’t, they won’t. It’s the event design that needs to be right. The Kochi–Muziris Biennale was the inaugural Indian biennale, and it was also the first opportunity I know where you could get to see serious volumes of contemporary Indian practice and come to some awareness of its details yourself.

Atul Dodiya, Kochi–Muziris Biennale, Kochi, Kerala, India, 12 December 2012 – 13 March 2013.