Traumatic acts and therapeutic structures: A few ideas in, around and associated with Stamm

by Jonathan Nichols & Amita Kirpalani

I

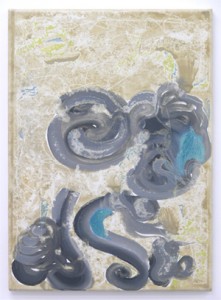

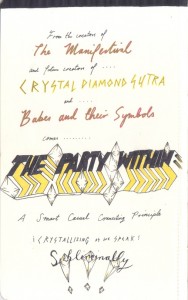

The idea of a ‘traumatic object’ is around and can be found lurking in conversations about dOCUMENTA (13). Between us this year, the language of trauma is closer to being caught up with what happens with art making and art writing. Which is slightly different.

As I read it, because I didn’t see it, dOCUMENTA (13) used broader associative ways to identify traumatic objects: stories etc. (For instance, I suppose Lee Miller didn’t pinch Hitler’s toothbrush.) Association is key. Early on we introduced in Stamm Jan Verwoert’s take on trauma and art making as to do with a mechanics of empathy, which is closer to the way I understand it.

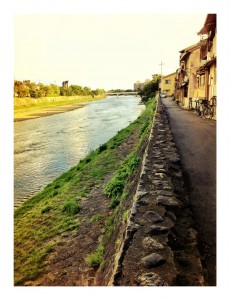

The idea of place is important here. The traumatized object is something which suffers the pressure(s) of place. Outward as well as inward pressure. Stamm was established to apply the pressure of regular writing against exhibitions which occur largely within a few city blocks. Supporting this set-up is a collection of voices that clash, jar and don’t quite align. Not to represent a cross-section, but rather to associate, since most of us are looking not only within but, crucially, beyond a particular local ‘scene’.

II

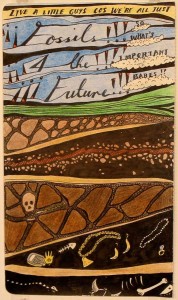

Hal Foster suggested recently that we are fatigued with a rhetoric of avant-garde ruptures, breakings, tipping points and are now preoccupied with stories of survival and persistence. I’m seeing the vogue of ‘old and new art’ together as to do with seeking a clearer sense of temporality in art making (time and space). This is also though a retreat in part from contemporary practice. Hal Foster says the times are for changing, and ‘radical new’—in the sense that he holds to modernist values—is not being looked to so much post-2008.

III

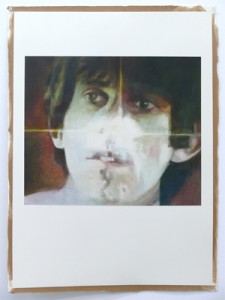

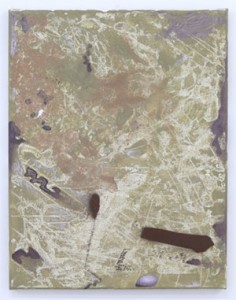

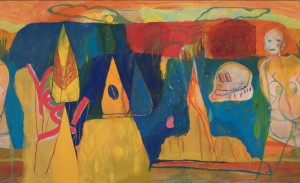

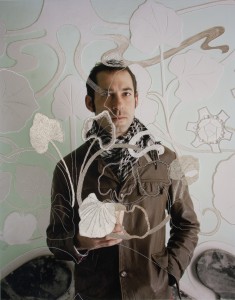

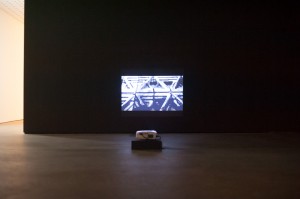

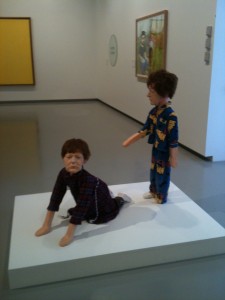

We’ve been talking about process as trauma and regularity as therapy. The same way an exhibition space offers a regularity of event and venue. I like the idea of the exhibition space operating as the office, rather than the studio operating as the office. Labour within the studio is trauma but the presentation of an object that has been produced in this context compounds the issue.

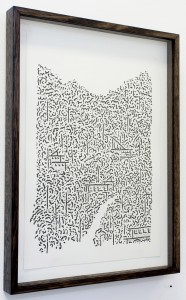

Heightened, compounded and, perhaps worst of all, very known: an exhibition space is mutable and contains a show, but as well it can impose its character, it’s a mutable enterprise or can, on occasion, background a work in ambivalence. In the way that a gallery is a kind of stave for the art, the idea of the text is a stave too. It too can hold up an artwork and offer its own rescue. It can also shut it out and down of course and play the games of hierarchy: a counter-discourse of ‘destruction’ and destructive acts. A therapeutic structure, be it writing (as in Stamm) or an exhibition or gallery, can rescue the traumatic object.

IV

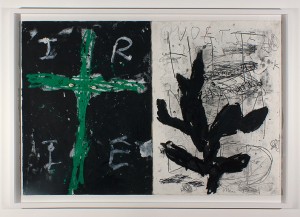

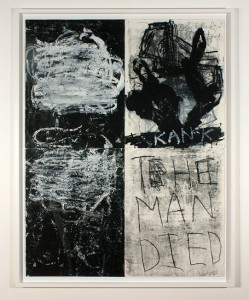

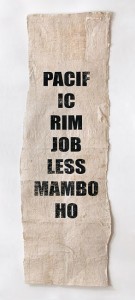

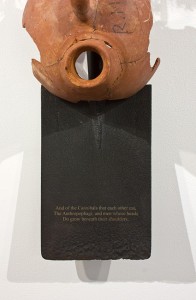

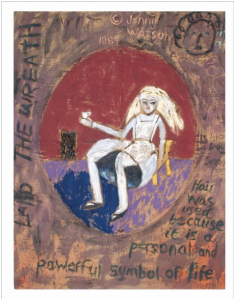

If writing more generally is proposed as a therapeutic structure, we might look at art and artists that further interrogate this idea of collaboration and direct reference to therapeutic, cathartic structures. Some favourite examples:

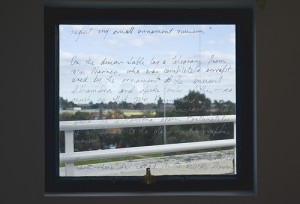

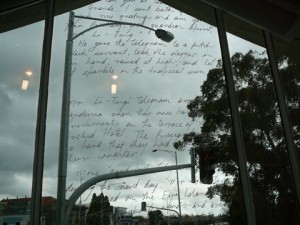

The Telepathy Project

A Constructed World

Nat & Ali’s therapy session screen at Hells

Sophie Calle

Marina Ambramovic

Stuart Ringholt

Anastasia Klose

Chiara Fumai

The greatest tragedy of President Clinton’s Administration, Mike Kelley

Otto Muehl

Mike Parr

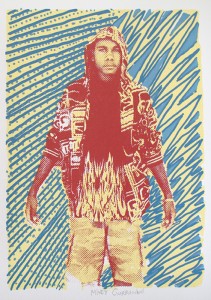

Dani Marti

Rose Nolan

V

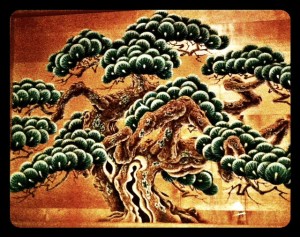

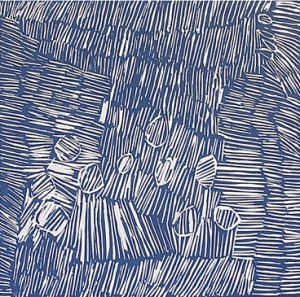

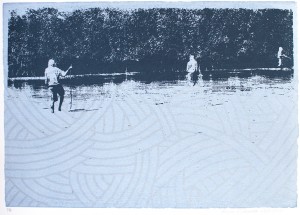

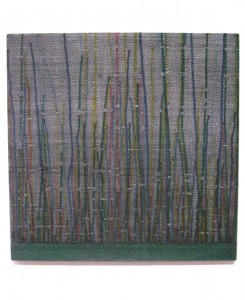

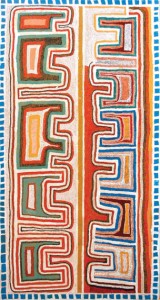

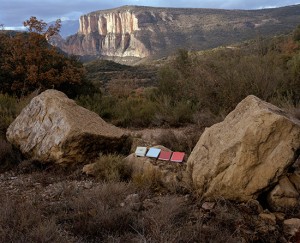

Cairns. Little stacks of rocks, a kind of tourist graffiti that populates historical monuments and natural wonders. These are temporary markers of an individual experience. But there is deceit at play too. Technically this individual act is a collective experience and the residue, the cairn, undoes the ‘naturalness’ of the vista.

This style of publishing—a collective, monthly posts, 300-word count (rarely adhered to), with few other ‘rules’—is its own little stack of different-sized pebbles. Perhaps to be knocked over soon after its construction, imminently dismantled. Marking the viewing, the experience. Sometimes contributing to it, sometimes littering. Balanced and not.