Good behaviour

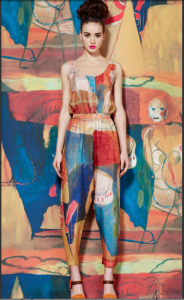

In preparation for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, 4 million households in Beijing received etiquette guides which focused on things like how to queue correctly, that when standing in public one’s feet should be in the shape of a ‘V’ or ‘Y’ and, my favourite, that there should be more than three colours represented in any one outfit. While in Beijing last month as part of an ICI Curatorial Intensive I also learned that, post-Olympics, less specific behavioural guidelines linger in the city. The word kequi, for example, features on street signs and noticeboards mainly around tourist attractions. It was explained to me that this word roughly translates as ‘good or ideal behaviour for a guest’.

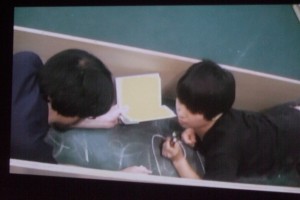

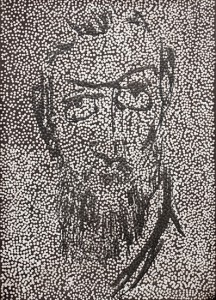

We were warned moments before meeting him that what Ai Wei Wei hates more than Communism are pretentious academic discussions about art. We were also warned that there was every chance he would be less than chatty due to the fact that police had, days before, confiscated his passport once again. We were encouraged to ask questions instead of hanging back for a lecture. Rather than a bad mood however, it was the large white arc of a scar etched across the back of his head that I first noticed about him as we followed him through the courtyard, and into the studio itself. Ai Wei Wei designed the complex, a modernist concrete bunker of sorts, in which we sat. Twelve (intimidated and more quiet than usual) curators to one artist (and two cats) didn’t feel like an honestly productive or a productively honest ratio.

And what eventually and surprisingly emerged from the initially lack-lustre Q and A, was a lengthy conversation about long-term collaborations between artists and curators. Mori Art Museum curator Mami Kataoka spoke of the pressures of being the artist’s eyes and ears at sites where Wei Wei’s travel was (and continues to be) restricted. It’s totally personal. Beyond constraints such as gaol time, which ignites a project with a specific urgency, was the sense that simultaneous development, and in-depth understanding (theoretical, practical and methodological) sit in sustained communication, if not collaboration, over time.

This studio visit was conducted with Philip Tinari, director of Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art, Beijing, and Kate Fowle, director of Independent Curators International, New York, co-hosts of the ICI Curatorial Intensive with 12 participants, and 2 of 12 guest speakers, Rodrigo Moura, curator, Inhotim, Brazil, and Mami Kataoka, senior curator, Mori Art Museum.