invisiblevisible (with Emily Cormack)

OK, the document you sent to me had seven lines in it. And about twenty-six words. Is that enough? As I said it was just a start. Is this part of our writing together? The initial bickering? Anyway, it seems when talking about works like these, you and I want to talk about them as props that hold the story, the frameworks of an idea.

[Assertion] The content seems not really that important.

[Discension] I’m not so sure I agree, are you suggesting that structure can never also be content?

[Clarification] You know I am a big believer in form following function. Form parallelling content. It’s just when the two get out of balance and I am suspicious. Perhaps now, the great framework, the language of sculpture has become enough. Like substitutes or summaries for research and feeling.

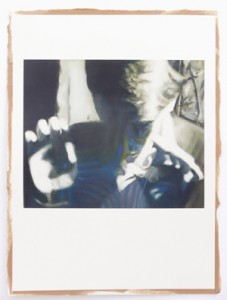

[Give me some examples] Powder-coated steel frames with small incidental-seeming objects flung casually here and there. Screen-like props, anthropomorphically scaled, and draped with fabric that flutters, leather chain, plastic chain, a designer chair here and a banana there.

[Assertion] It’s kind of frustrating to feel like you are seeing the same work over and over again, but maybe it is also training to look harder, to acknowledge the intricacies of the visual language that is being developed. [Question] What do you think about that?

[Answer] It makes me feel like I am driving down a cul de sac in a new housing estate trying to differentiate the different styles of Delfin homes on offer. Wow, check it out this one’s got eaves!!!

[Opinion] But you can hardly blame the sculptor. Just like the Delfin homes. They build them because people love them. Need them. Want rooms similar to their neighbours’ because everyone’s got the same stuff to put in them anyway, with just enough space or shelving for some kind of individual flair.

But then, perhaps, this is what they’re about. A kind of self-reflexive critique of ourselves and the land of structures and frameworks, with very little flow through, that we dwell in. The world of form being well over content. [Assertion] Maybe we are all talking about the same thing?

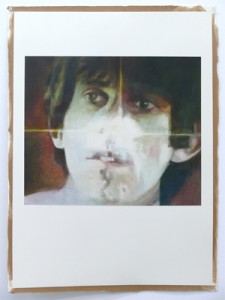

Here I think this is about your desire/our desire (compulsion/mental illness) to find narrative but of course this is about the sculptural, the essential, the stripped back.[Interruption/over-talking even] sculpture isn’t always about the essential do you think? But that’s off topic …

[Response to over-talking] I half agree. But when it becomes about the elements of the work—the ‘base’ materials—isn’t that essential?

[Sneeze] Maybe this is about the non-verbal. I know you are going to say art is about the non-verbal (of course!).

[Assertion] But maybe this work takes us back to a tangible/literal association with this. And these works create their own network, which looks like a big ol’ net. Cross-pollinating one another with content.

[Ascension] You mean like these sculptural frameworks are the hand gestures or leg crosses of the sculptural nomenclature (that’s not a question).

[Concession] Interesting idea.

[You always say ‘interesting’, when other people might say ‘great’—you don’t mean ‘interesting’, you’re fobbing me off.]