Obiter dickta

The camera transforms its operator into a creep. The eye not pressed to the viewfinder holds a wrinkly squint. So the camera operator always appears as if she or he is semi-disgusted with what has been found in or orchestrated especially for the viewfinder. Long hours, for some, are spent like this. The squinting eye is only partially idle, guiding … seeing and not seeing … idling. And so it’s with this eye that we also witness Lane Cormick’s performance, within a busy exhibition opening, via which we are party to many other acts of observation, there is so much looking.

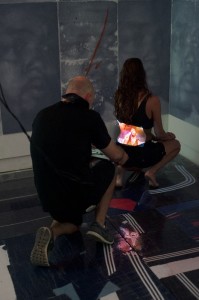

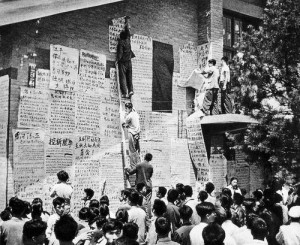

Nina Simone begins her performance at the 1978 Montreux Jazz Festival by adopting a graceful deep bend in a long black dress, her hands held in supplication for a few moments, while the audience applauds. Once upright she distractedly begins singing to herself or perhaps just mouthing the first phrase before she takes the microphone to begin performing. Be my husband and I’ll be your wife. There aren’t many shots of the crowd, most of the footage is a close-up of Simone’s face and there is one lingering shot of a cameraman hovering in the background, behind her grand piano. Be my husband and I’ll be your wife. Cormick holds a projector, displaying this footage of Simone now rendered orangey black, and he aims it at a woman I’ve never seen before. The woman wears a black singlet tucked up into her bra, so that her stomach and her lower back are bare, and available for projection, sorry the projection. Simone singing. Love and honor you the rest of your life. If you’ll promise me you’ll be my man. Simone’s eyes are wide open and wild. The woman holding and not holding this footage on her body as she moves across the space, she looks somewhere, but not at us, and not around the gallery and not at Cormick. If you’ll promise me you’ll be my man/I’m gonna love you the best I can.

The exhibition space, during the performance, compressed the viewing experience, more so than usual: in addition to the audience of bodies who lined the walls and occasionally shuffled past Cormick and his performer, the repeated xeroxed portrait of ‘lost’ soul musician Lee Moses served as a kind of compacted, coded and symbolic scenography. The floor was also recovered in a collage of cut-up Adidas tracksuits, black with white triple stripes, perhaps a reference to Jesse Owens, or perhaps not. Repetition and doubling served to draw the sculptural and the performative elements together in a loose twirl.

Cormick’s projection was a careful and relentless shuffle, to his subject’s eurhythmy or, even, whim. Over the 40 or so minutes’ duration, a twisting and turning to the comparative stillness of our spectatorship didn’t serve to fully communicate the connections between all these portraits: Cormick’s self-portrait as projectionist, the woman as dancer and as projection screen, Nina Simone, Lee Moses and even we, the audience, caught in the viewfinder of the guy documenting the performance.

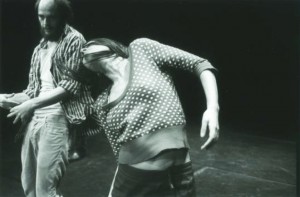

Last month many of us experienced Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Trio A’ ‘transmission’ sessions in Perth, Melbourne and Sydney, as well as Kaldor’s 13 Rooms, where the celebration, reinterpretation and recontextualisation of 1960s performance practices and aesthetics (rather than politics) have been given an overwhelming cross-institutional tick. By contrast, Cormick’s performance is a refreshing turn about the room because there is sex in here, even if it’s not good sex. The performer is hunted down each time, while successfully falsifying relaxed and languid movement, playfully and seductively enacting pose and repose. But maybe that’s just your writer inferring seduction, based on at least one instance of slow motion tousling of her own hair, her exposed midriff and her disinterested gaze loosely focussed on the middle distance, that even regular opening-goers are never easily able to fake.

Lane Cormick, Janis, TCB, Melbourne, 27 March – 13 April 2013.