Vogue-ing for the dictaphone: Alex Martinis Roe

One thing I’ve learned is that you can’t undo a blurt or even a short rant. Perhaps because I speak to think, like most of us do … right?

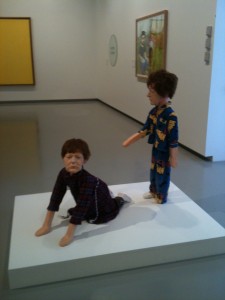

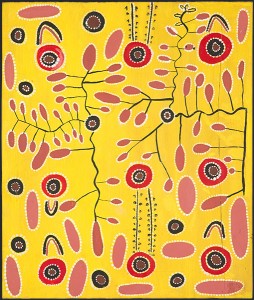

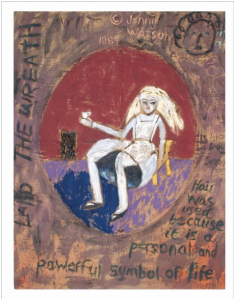

On Friday February 17 from 2 to 4:30pm, formerly Melbourne, now Berlin-based artist Alex Martinis Roe facilitated a workshop she designed as part of her work for Post-planning, an upcoming group show for the Ian Potter Museum of Art, also including work by Damiano Bertoli, Julian Hooper, Andrew Hurle, Michelle Nikou.

A similar workshop had been staged by Martinis Roe in Dublin as part of her solo project at Pallas Projects and all the invited participants were briefed about this in the invitation. The workshop involved, as stated in the email invitation, ‘three main tasks, which are undertaken in pairs. Each of the tasks involves discussion of the specific relationships each participant has to the female authors that have been influential for her-him, and involves different ways of working together and listening to one another’. Upon reading this, all of a sudden can’t remember anything I’ve read … ever … total blank.

So I started to think about what a workshop was. A room or place where tools are available to repair other things. Was I going to be repaired? A place where things are produced. Was I going to take part in making someone else’s work? An activity which goes into effect in order to create or deliver something, ‘a deliverable’. Oh no.

Once inside the Ian Potter Museum, the spaces were cordoned-off, tables were set around a central node which included Martinis Roe and elaborate recording equipment. Part stage, part sound desk. The welcome by Martinis Roe was clear, faultlessly professional and friendly.

But then it became about us (not me, as I’d first agonized over) and as we filled out the first form, on which I had to write my name, it occurred to me that this workshop emulated my own paid work in many ways. These forms and instructions followed would potentially be used later or not at all.

What this workshop seemed to produce in humility, affirmation, sharing, it redacted in documentation, prop-making and chronicling, but I reflect now on how we hold onto our ideas, our starting points, what we return to and our false-starts.

Alex Martinis Roe, Frameworks for Exchange Workshop, Post-planning: Damiano Bertoli, Julian Hooper, Andrew Hurle, Alex Martinis Roe, Michelle Nikou, Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 31 March – 22 July 2012.