Huh

Last year in September, JJ Charlesworth wrote a relatively short opinion piece for Art Review titled ‘At what point does nothing become too much of a good thing?‘—a pointed meandering that refers to Object Oriented Ontology (OOO hype) whilst questioning the ‘dematerialised, postindustrial rhetoric’ of Tino Seghal.

In between all this questioning of material-based culture, the market and overproduction what about the ‘thingness’ of words, verbal exchange and speech; of daily exchanges and their value; what is shared and how it becomes action—the materiality of language.

Samuel Beckett spoke about the limitations of this and language. In his famous 1986 made-for-TV teleplay ‘Quad I & II’ we have the visual boundary of these ideas played out. Quad’s script could be read as a mathematical pattern or a diagram—a thing—the material manifestation of something unspoken played out on a stage and presented en mass via television. Ungendered cloaked mimes rhythmically stepping-out a preprogrammed loop, leaders alternating, order defined by the boundaries of a square stage, this in turn echoing that of the square box of televisions from that time. The centre only ever circled (so too speak), as if to arrive or acquire desire, would only serve to make visible what we the viewer and unnamed collective might already know. Beckett’s stage play is as such, a kind of gesture towards us—a pattern we can interpret, a rhythm we might recognize—potentially boring the arrangement becomes a narrative without words and somehow contains shared meaning.

Life and times begins with about a five-minute musical prelude—somewhat Sufjan-Stevens-Illinoise in its arrangement and then …

um

is sung.

I’m not sure many musical theatre scripts begin with um, a pause filler dependent on place and perhaps time. (Americans use um and uh, whilst the British might use er and erm. I think we use a combo. I’m fond of the Japanese ano and eto.)

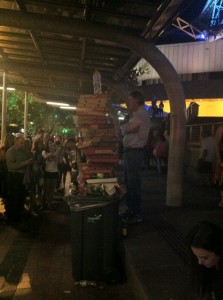

Life and times episodes 1–4 was performed on sequential nights and in its entirety during a ten-hour-day long marathon performance which included a BBQ and brownies cooked and served by members of Nature Theatre of Oklahoma (NY) during the 2013 Melbourne Festival.

The duration of the performance eventually reveals a narrative, but one that involves repetition, boredom, and choreographed and melodic improvisation. Simultaneously theatre and not-theatre, Episode 1 opens with three female cast members each singing a different part of a recored narrative. References to first person and third person pronouns move with each character. When the female cast members are replaced by their male counterparts, so too do the gendered pronouns—one person’s story becomes many. As you wonder if anything will happen, and boredom sets in, it is ruptured by the semi-fascist grey uniforms worn by the cast, the occasional glance they throw you, or the rigid mass-spectacle-type-semi-democratic-choreographed moves.

Fatigue and boredom are shared by both the actors and the audience, perhaps too by those playing the live score …

Oh my god …

um … I’m like a very serious baby.

um and ah um.

ha ha ha

It’s a kind of a lol IRL YOLO performance that reflects on someone’s (anyone’s) life story from birth, mostly sung by a cast that somehow maintains momentum and stamina without the usual verse-chorus-verse-structure. Unlike Quad, the repetition is inconsistent, or less obvious from afar—more differential calculus than linear equation and more sculptural painting performance gig than theatre—the formal space of the Playhouse transformed.

Come on Julie, come on—is chanted semi-Appalachian—think ‘Down in the river to pray’.

It was like so beautiful—returns intermittently throughout the performance like an off-beat refrain.

Day-dreaming seems like an OK thing to do during the performance—the OK singing, the OK dancing and the OK script kind of merging to form a kind of familiar soundtrack, albeit new. By the 3rd and 4th episode—more ‘Days of our lives’ or ‘Bold and beautiful’ in its aesthetic (rather than the minimal post-Soviet uniforms of episode one, and RUN-DMC-multicolour-tracksuits of disco-backing-tracked episode 2), you might be looking at the audience around you. Watching them, instead of the stage, as they laugh, cry, walk out, fall asleep and/or sigh in response to the almost-acapella-absurdist-and-readymade-script (the (soon to be 16) episodes are derived from a phone conversation between an unknown to us story-teller and the OK Theatre directors Pavol Liska and Kelly Copper).

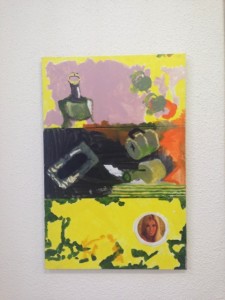

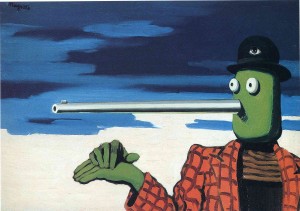

As with Beckett’s Quad, story is rendered irrelevant whilst language is stretched—formal foredom—like Baldessari throwing balls in the air to make a perfect square, or Taree and Ronen’s coloured Venetian blinds and Sam George’s Sony Bravia painting of every letter of the alphabet overlaid.

Art critic Jerry Saltz’s analyis of Kanye West’s video in the article ‘Kanye, Kim, and the new uncanny’ if set alongside journalist Chris Hedges’ ‘American psychosis’ which asks what happens to a society that can’t distinguish between reality and illusion presents us with a problem—that of distinguishing between varying kinds of representation, often conflicting. With Tony Abbott’s LNP and David Cameron’s Conservative party both erasing parts of their history from the net last week, this formalist boredom is perhaps a symptom of an unspoken shared social.

One half of the Life and times director-duo, Pavol Liska, originated from Slovakia and was trained in the mass spectacle performances of the Soviet-run state. It was the theatre companies that led the strikes leading to the 1989 Velvet Revolution.

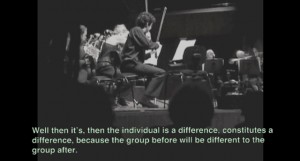

In Ranciere’s text The aesthetic unconscious, he attempts to position his idea of the aesthetic regime in the context of the emergence of psychoanalysis and the order of representation. It is described as being the relations between what is said and what can be seen, and the set of relations between knowledge and action.

Amidst a plethora of representations our shared ‘trying to say everything at once’ is perhaps very similar to a potentially never-ending almost melodic and almost performed opus, huh.

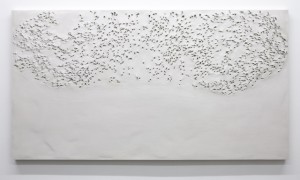

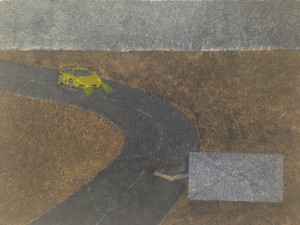

History is our audience (Craig Burgess, Marcia Jane, Taree Mackenzie and Ronen Becker, David Chesworth, Dirk de Bruyn and John Nixon), curated by Kelly Fliedner, WESTSPACE, Melbourne, 22 November – 14 December 2013.

Sam George, just for now, TCB art inc, Melbourne, 30 October – 2 November 2013.

Life and times: episodes 1–4, Nature Theatre of Oaklahoma (US), Melbourne Festival, Arts Centre Melbourne (Playhouse), Melbourne, 22 – 26 October 2013.