Doing it right: Recorded responses to ‘Art as a Verb’

On June 11, 2015 I visited Artspace in Sydney’s Woolloomooloo for the exhibition Art as a Verb. Whilst there I decide to make ‘voice notes’ on my iPhone, perhaps as a live commentary on the experience of seeing. Playing them back, I realise that I’m yet to master this technique, but in addition to a lot of heavy breathing they include:

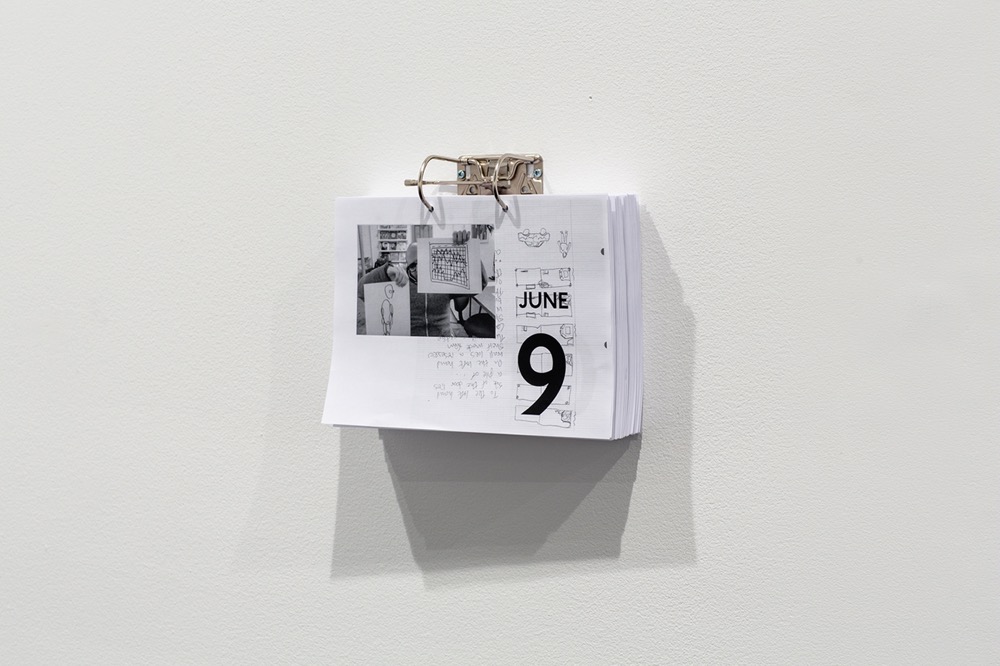

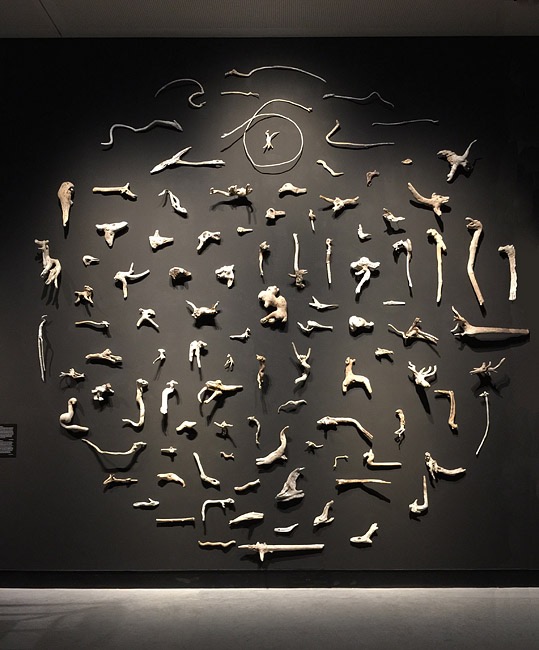

“Ryan Gander’s The Medium [pause]. Works in prominent and unexpected points in the gallery speak to me of good ways to think about exhibition making and audiences looking.”

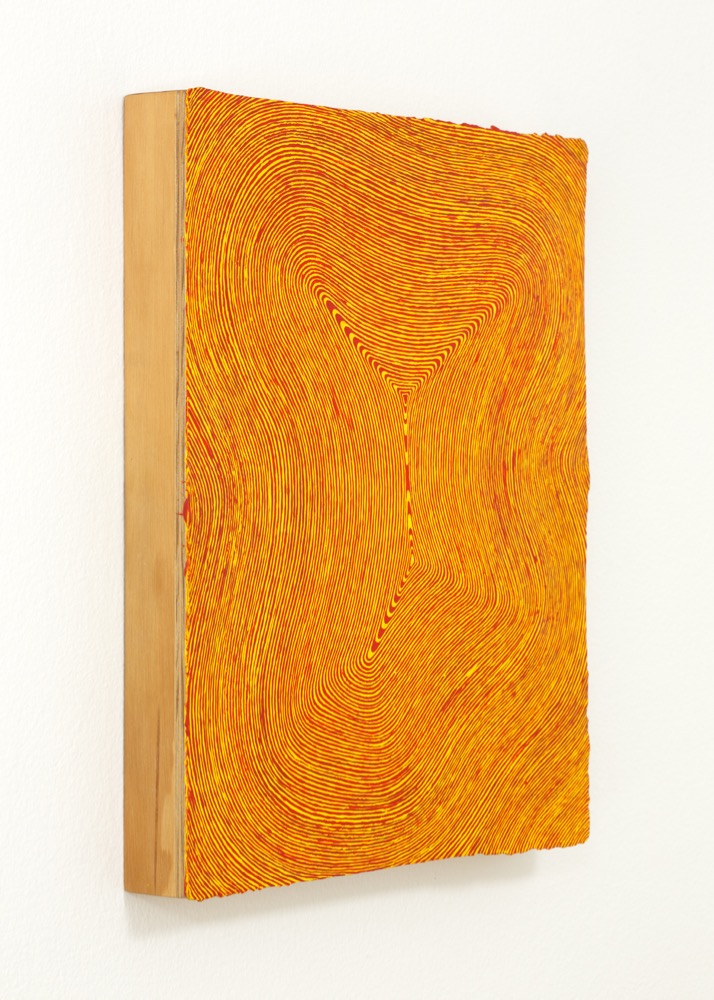

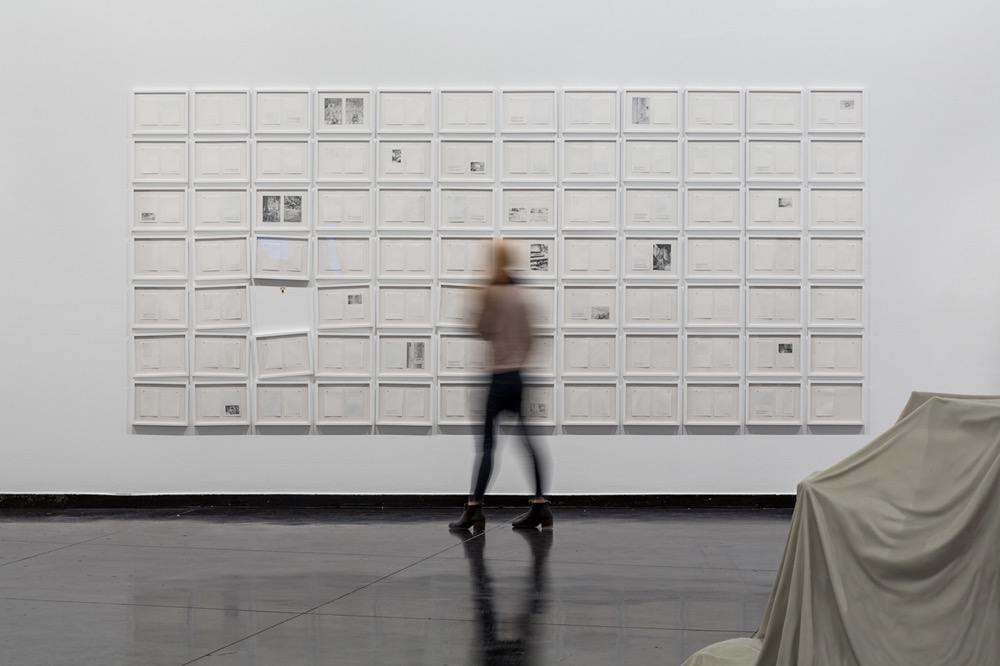

“Artworks are stand-ins for people … there’s real humanness on display … These works remind me of myself, people I know. Works sharing something familiar are bound to do that. [There’s] something profound about the repeated process… ”

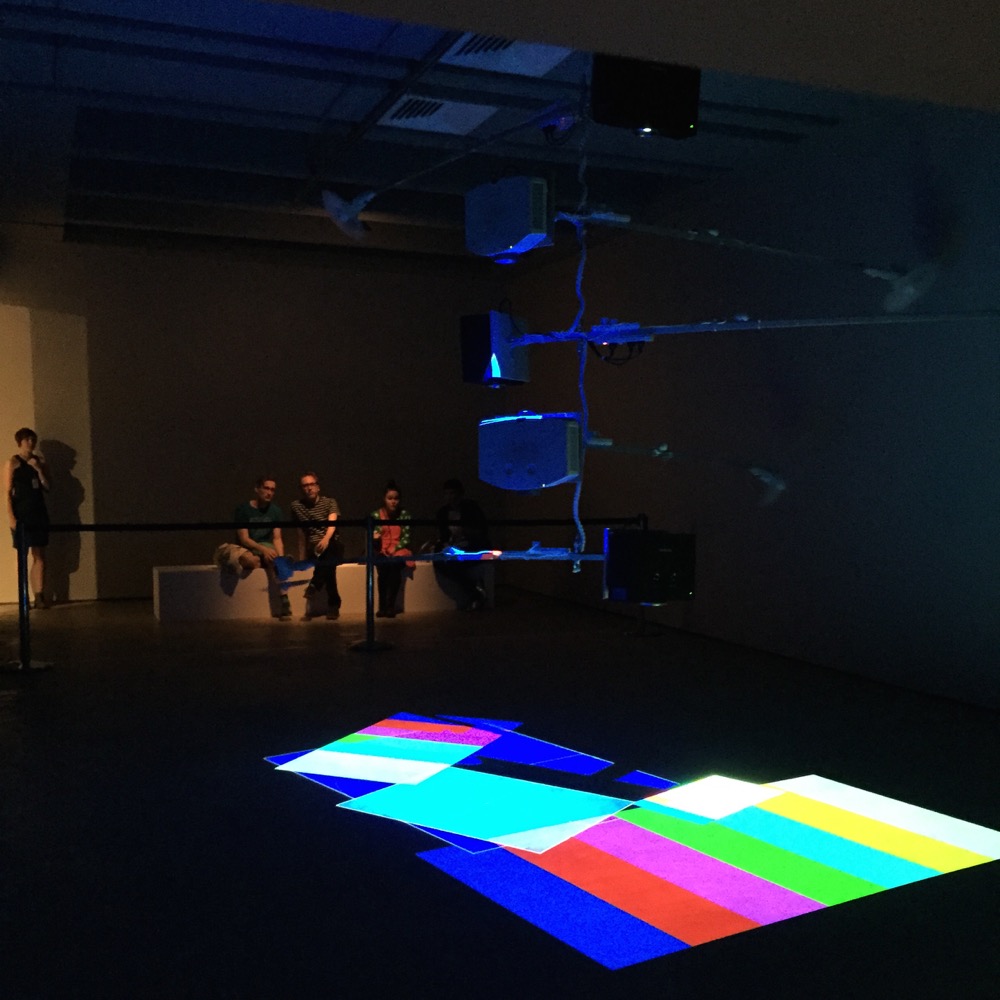

“There’s a grouping of seminal works by artists such as Marina Abramovic and Vito Acconci … sit[ting] in the back of the gallery, displayed on monitors in a circle … it’s like a central nervous system … like a historical backbone to the show. [This grouping] … makes these works feel stronger, more important, like ‘going home’ to visit your parents. Wait, what does that mean? Note to self, be nicer to Mum and Dad.”

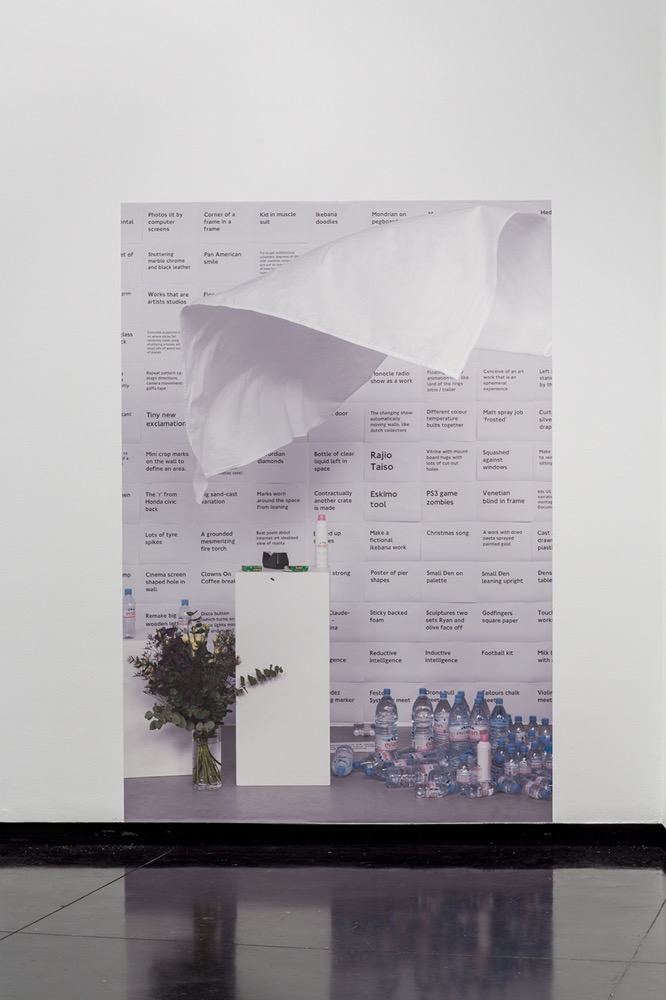

“I should make a list of all the verbs within the show … looking, smiling, eating, learning, clapping, [pause] singing [trails off]”

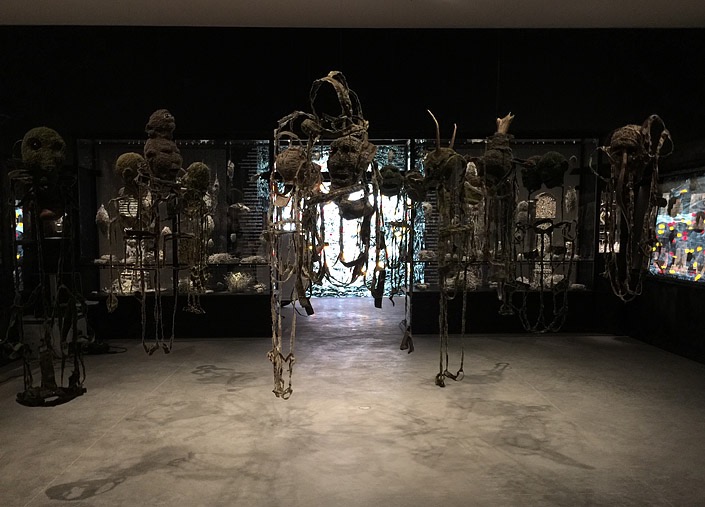

“Being surrounded by so much ‘doing’ … makes me question what I’m doing, what I SHOULD be doing. [pause] Keep going.”

“This show is like a maze, a guided tour and a labyrinth. I like it.”

“It’s like I am the final work in the show; it’s like I am a verb!” (Embarrassingly, I am not alone in the gallery when I say this out loud.)

At the end of my visit and when I feel like I’m done, I linger in the foyer to enjoy Ceal Floyer’s Til I get it right, a sound work that’s followed me around my whole visit. It’s on repeat both in the gallery and, happily, in my head long after I leave.

So I’ll just keep on/ ‘til I get it right…

So I’ll just keep on/ ‘til I get it right…

So I’ll just keep on/ ‘til I get it right…

Art as a Verb, Artspace, Sydney, 4 June – 26 July 2015.

![Former Wittenoom Road Sign. Photo: Five Years at en.wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (sa/3.0], Wikimedia Commons](https://stamm.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2_SW.jpg)

![Port Sulphur. Photo: Dr Warner (Flickr: IMG_4276.JPG) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://stamm.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/3_SW.jpg)