Bradd Westmoreland—wet

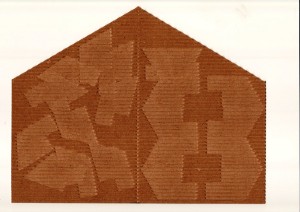

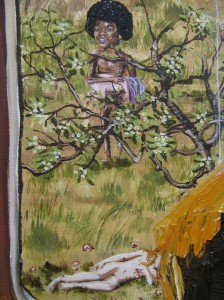

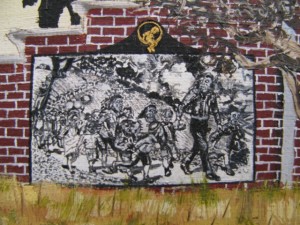

In January 2009 Bradd Westmoreland painted this crazy huge frieze titled War & peace around three walls of a small studio space I’m attached to in Fitzroy as part of a very local, very diverse, summer series of impromptu weekenders. The full catastrophe was equal part dance of life and cycle of destruction painted over a couple of days. The weekend before, Alicia Frankovich had roped and literally harnessed the entire studio building in a live performance titled Lungeing chambon. It too was a type of dance.

Too few ‘wet’ artists manage to connect with or show an interest in the main settings of contemporary art practice. They are happiest being all stoic and hog-tied to the symbolic conditions of the studio, thinking they are on a higher plane, or something like that. They don’t cheerfully fit the concrete politic contemporary art finds easiest, but also strangely don’t engage well with its impermanent and haphazard conditions. Even a word like ‘painterly’ once actually suggested a relative idea of clarity rather than an exhaustively complete one. Westmoreland’s War & peace frieze was a rare example in Melbourne of an artist ‘crossing the river’ so to speak.

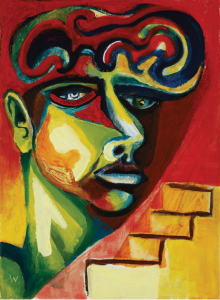

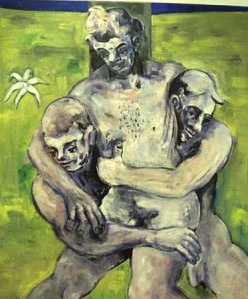

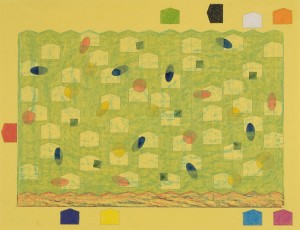

In 2010 Westmoreland painted a second wall painting at the Ian Potter Museum of Art for the exhibition There’s no time. The painting, Night’s bright song, was in a room alongside John Spiteri’s early works on glass and ‘calendar’ paintings on board. The motif Westmoreland constructed was like a gigantic snake-charming scene. He had again carefully flipped onto the gallery wall the working routines he’d established in the studio, something that provided a loosely held subjective presence in the work.

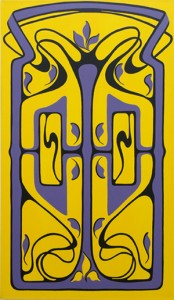

Each of these two wall paintings were curious if for no other reason than their mechanisms involved nothing of the more familiar ‘wall drawing’—architectural notation or string piece or photographic projection—de rigueur structural incursions all. Westmoreland’s art is more to do with the absence of a premeditated structure or conception or approach than just a casual, loosened or relaxed art procedure. But of course that is not completely true either. There are clearly broader codes at work and repatriations of a sort. For instance, at Westmoreland’s Niagara show earlier this year, it dawned on me (belatedly) how close his paintings are to the work of the late Peter Walsh. The precepts seem to play out in a similar way.

Bradd Westmoreland, War & peace, Beyond the Green Door, Melbourne, summer, 2009.

There’s no time: John Spiteri, Mira Gojak, Karl Wiebke, Bradd Westmoreland, the Ian Potter Museum of Art, the University of Melbourne, 17 November 2010 – 13 February 2011.

Bradd Westmoreland, In the light, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, 7 February – 3 March 2012.