Sadie Chandler: Café society

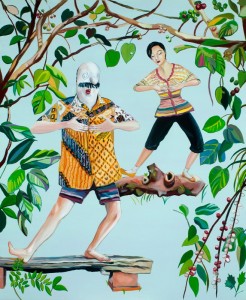

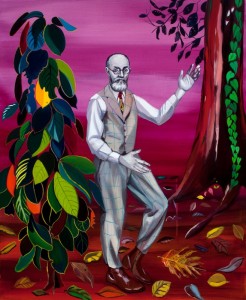

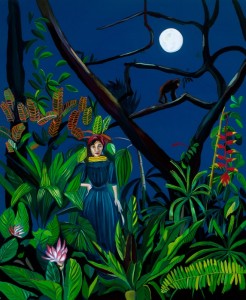

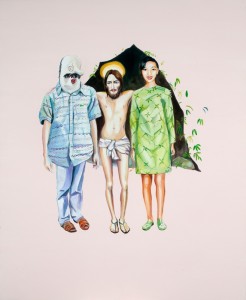

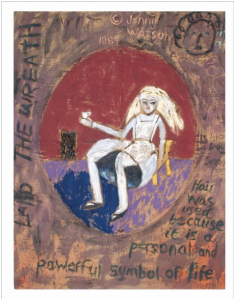

Figures and faces have always been a feature of Sadie Chandler’s iconography. From her varnish-obscured portraits of an anonymous, genteel European ancestry to her pre-Mad men mad women strutting their stuff, and the latest forays into the group portrait as social document, art and life converge.

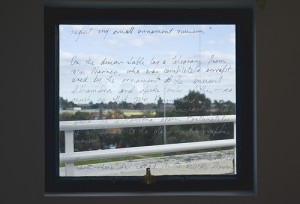

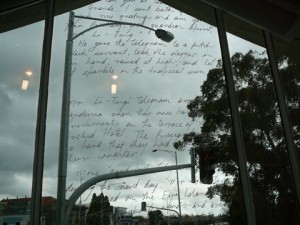

Most recently, Chandler worked on the Moreland portraits, a public art project in the Victoria Mall, Coburg, in October 2012. A related work is North, a 10 x 3 metre papered wall of drawings for North Cafeteria on Rathdowne Street, North Carlton, with opening hours more generous than your average art gallery or temporary art project.

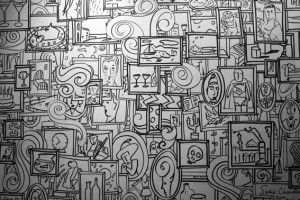

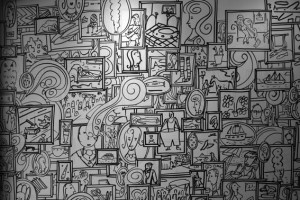

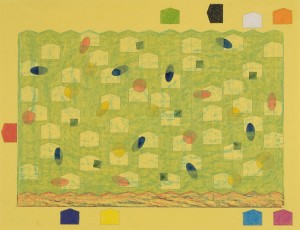

Here, taking time out from the business of life, one can enjoy the view of people coming and going alongside those fixed to the wall more permanently. Going soft in the heat of a sultry afternoon I feel a bit like the mad woman in The yellow wallpaper disappearing into the background. Familiar figures and faces pop up in a seemingly endless array of frames, all different but somehow the same, reduced to an all-over signifying, simplified line. These figures stand tall, full frontal or in side view, cut-off like a portrait, or semi-inclined, stretched out like an odalisque or participating in some kind of action. With their pointed gestures, striking poses, look and dress and all the right accoutrements, a life in pictures is played out before my eyes.

I recognise a lot of them from art history: a Picasso portrait, a cubist still life, a Matisse interior (the one with the goldfish), a de Chirico scene in a Renaissance town square and what looks like a flagellation or some other dire scene from the Bible. There are culinary delights, scenes from nature, house portraits, people portraits, a boy dressed as Superman. Some of them more serious: a person standing in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square, a statue of Saddam Hussein being toppled, a random person lying dead in the street and lots of women crying. This is a society portrait with everything possible brought into the frame. There’s genre and gender, and current affairs, and lots of art references to go on. And then there is the line, always the line, like studies in motion, composition, expression, and that characteristic Chandler curlicue flourish.

And here she is—the artist in person—joining me for cake and coffee. I just love that it’s Saturday.

Sadie Chandler, North, 2012, North Cafeteria, 717 Rathdowne Street, Carlton North.