de for

In the last month or so, we have seen leaders change, policies align and disgusting decisions imposed on the most vulnerable. Decline seems to be our modus operandi. If an empire is failing, how does it fall with the least possible pain?

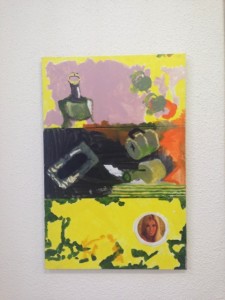

Harriet Morgan’s exhibition with the same name, Decline at Top Shelf above Deans Art in La Trobe Street might have been asking the same thing—an omnipresent apocalypse with a glass of champagne. Nick Austin’s paintings of flying envelopes and Kate Smith’s three-part painting Art school point to a past, a kind of neo-nostalgia: one more melancholy than the other—a nuanced picture and unrecognisable painted forms in spaceless-languid-yellow. Alex Vivian’s Dirt swatch is a sliced soccer shirt flicked with filth and fixed with hairspray skinned over a neo-faux-doric-columned-new-bone-china-serving-dish registers painting in its past-particle-present—the ambiguity of polity evident in an array of decadence.

New improved qualities …

… reads the text on Janet Burchill and Jenifer McCamley’s painting accompanied by a chair.

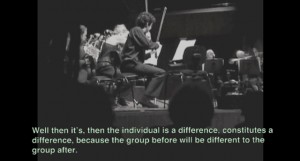

Helen Johnson’s video as long as a pop song has a group of nameless voices discussing Badiou and Brecht in a context that’s not ours to be privy to. We see, not hear, violins played and a cat looks back at me spliced after footage of Karl Marx’s grave. I look down to my phone, a ‘fact’ reads: other than humans, cats are the only other species which likes getting things for free. While wondering what this might mean, the analytical screen and self-conscious spoken words remain synced, ‘I keep making the same point, fine, but … I don’t understand what an individual is. I don’t know what it is … ‘ But it is in the opening lines, ‘But aren’t the militants here precisely trying to prevent the young militant from taking this path’, that we find the dissension and the doubling in Decline.

To depose is to get rid of, dismiss or displace. De-pose on the other hand, might infer a colloquial reference to the stance of someone captured on The Satorialist blog. In either form, power is undermined—that of the leader by an action or that of the image (and beauty itself) by language.

Caligynephobia is an irrational fear of beautiful women, callophobia is an irrational fear of beauty and scopophillia is the ‘love of looking’.

The first may be evidenced in cinema, and the latter perhaps found in art: Abicare’s objects declare a different type of decadence than that which is found in Decline.

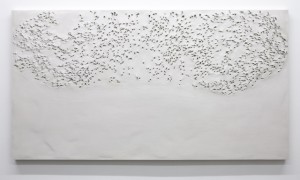

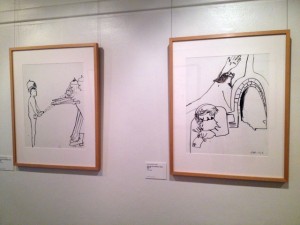

Decadence (Medieval Latin for ‘decay’) in Abicare’s work appears in the subtle arrangement of objects that point to one another and us, creating a space of suspicion between. A chair in the corner of the room. A cast of clay the size of a table-top, perforated by studio-based archery lessons framed on three sides with stainless steel and the other with bronze. Looking back at it, on the mantle above the disused fire-place rests a small framed photo of a woman wearing a beautifully made coat—the sartorial sign—that also hangs on a coat-hanger as you enter the space. In the photographic image, behind the woman modeling, hangs the perforated clay, exactly as it does now, as I the viewer stand, minus the coat, the build and the photogenic smile. The aforementioned frame is mirrored, but to scale. Before the mantle, in front of an unused fire-place, the stainless steal and bronze are echoed again but inverted. A silk wool scarf that depicts a golden retriever and her double is placed, not thrown—its material more vulnerable and volatile than the metal one usually expects to be used for a screen. From the vantage point of the chair, one sees all and all sees one.

Go-see is the models’ audition, success is not predetermined. A trophy-pose is held by the winner, failure is for another time.

Attention to detail, these fragments from a narrative, un-timed objects re-appearing and re-occurring. Power. Desire. Target. Capture. Game in all its forms. Fair and unfair.

Love of looking. Fear of beauty.

Fear of beauty. Love of looking.

Décor starts with de.

Decline (Brent Harris, Helen Johnson, Luke Holland, Joshua Petherick, Alex Vivian, TV Moore, Kate Smith, Dan Arps, Dale Hickey, Kain Picken and Rob McKenzie, Nick Austin, Fergus Binns, Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley, Lane Cormick and Tony Garifalakis), curated by Harriet Morgan, Top Shelf Gallery, Melbourne, 14 June – 14 July 2013.

Fiona Abicare, De-pose, Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne, 27 June – 27 July 2013.