I recently had the pleasure of a studio visit with Melbourne artist Colleen Ahern. Ahern is a talented painter, best known for her domestic-scale paintings that portray popular musicians of the 1970s and onwards. The works are skilful and filled with love: there is a tender thrum of fandom in their composition and a nostalgia in her chosen palette.

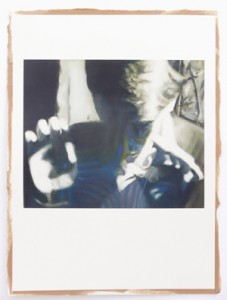

The last time we met, Ahern was working on a series of paintings based on photos she had taken of musicians performing on TV, on shows like rage and various music docos. The portraits captured her beloved musicians within the physical frames of the visual media through which we access music culture: a trippy colour burst; a line of static caused by the pausing of a VHS recording; a vague reflection of the viewer on the screen. Each portrait foregrounds a particular technological glitch. The series referenced the platforms through which we engage with our musical heroes and also the distance between us and them; the distance that allows them to remain accessible but untouchable, out of physical reach but close enough to gaze upon and listen to with adoration.

Ahern’s latest series began with the Neil Young song, ‘Cortez the killer’, which appears on the 1975 album Zuma. The song tells the story of Hernan Cortez, a conquistador who conquered Mexico for Spain in the sixteenth century. The song got Ahern thinking about what Cortez might look like and she began working on a number of paintings and drawings that depict her vision of the conquistador and elements of his escapades. These works continue Ahern’s desire to connect with musicians and make concrete and tangible her particular personal relationship to the music itself.

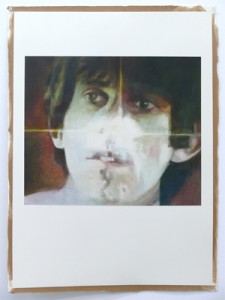

Where these new works get particularly interesting, and I think elusive in their purpose for Ahern herself, is that they have been the motivation for an extended series of drawings and paintings that depict numerous men, like Cortez, whom Ahern has never actually seen. These portraits are generated from Ahern’s imagination—they are not based on source images or narratives that she has created around them. The portraits themselves are as clearly depicted as if sketched from life and are motivated by her desire to create a series of faces that exercise her skill with various facial features. Each portrait embraces a different style: colonial, post-war Europe, contemporary. Each one is unique.

This series strikes me as particularly ambitious and challenging for a portrait painter. Ahern’s only source material exists in the slippery space of the mind and yet she is able to return to it, time and again, over a period of months. The works left me enthused, impressed and excited. But most significantly they left me wondering when was the last time that I could imagine, let alone capture the likeness of someone I had never laid eyes on before.

Ahern’s latest series is the stuff of true imagination matched by equal skill. Somehow, for me, it bridges the fandom of her earlier paintings with the anonymous characters of her favourite songs.