Talk it out

The performance show I should’ve stayed in Sydney for was Work out at the MCA. What I stayed in the MCA for was William Eggleston’s video work Stranded in Canton, 1974—documentary photography turns absurd trip that held me far longer than 13 Rooms. I shouldn’t have been surprised that a packaged blockbuster of performance work was upsetting.

The 13 Rooms problem that really stuck was substitution (there were a few others—see below). Substitution of the artist for another performer is problematic when the hinge of the original work was the artist’s reclamation of agency over her own body. This hinge is almost completely reversed in the re-objectification of women’s bodies through the replacement of a very particular body (subject) with any other hired female body (object).

When Abramovic pins herself to the wall, nude in a spot light, for indefinite periods of time she exerts agency. When a number of anonymous women are paid to do the job for her they become objects of a higher authority. About turn. It’s just not the same thing to watch someone paid to suffer, as it is to watch someone who chooses to suffer.

Repeat re Joan Jonas’s work.

The substitution problem isn’t specific to 13 Rooms, but put it in the mix with the contextless mist of that exhibition and the crux of the work is hard to find.

So, re-presentation of performance over time.

Tino Sehgal’s This is new, 2013, was the only work that shirked the curatorial heavy hand. The invigilator who said ‘O’Farrell comes out for gay marriage’ was the single performer in the show not choked by the shuffling factory line.

I’ve been waiting a long time to be Sehgaled, so there was that too.

Sehgal, who doesn’t allow documentation of his works and only verbal sales agreements, has got something in this no paperwork no photos please policy. Radical immaterialism. Radically visible evasiveness too.

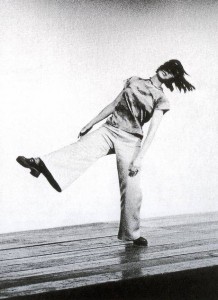

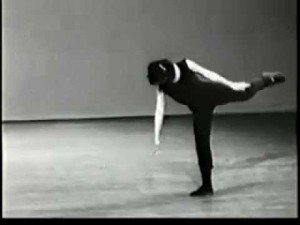

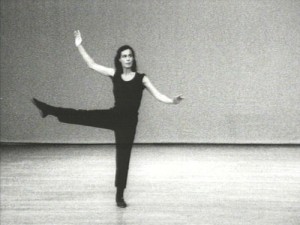

Re-performance and controlled transmission were also rolled out at the Trio A workshop held recently at VCA. Yvonne Rainer has a very particular way of facilitating the ongoing life of her iconic 1966 dance work. I sat down with Ash Kilmartin and Eliza Dyball to talk about their involvement in a workshop run by one of Rainer’s ‘transmitters’, Sarah Wookey. Eliza and Ash spoke of, and in, the language of Yvonne and Sarah—check in, tune up, take away.

Speech and the body. We talked about trying to close that gap—a gap that is wider for most of us than it is for a dancer. Eliza recalled an exercise where they each notated the dance and another participant then performed those instructions. The result was apparently often miles from the intention, which speaks of shift through the subjectivity of language.

Ash perceives in dance culture an acknowledgment that over time a work will change since it is passed down through the body and every body is different every day: ‘you’re not the same body two days in a row’. Sehgal and Rainer both transmit their work primarily through speech and both use the body and voice to either allow for or resist a shift in the work over time. Choreography expects another body to perform the work. And choreography acknowledges time. For those reasons Rainer’s and Sehgal’s works have a built-in protection against misrepresentation over time. Choreography not as a means (of instruction) but as a method (of making).

Sehgal controls the form, as Ash pointed out, and the content of the work is allowed to re-form each time it is performed. If the form of the other works in 13 Rooms were preserved, the content was all talk.

Postscript

My rant about 13 Rooms includes, and this is an architectural as well as communication hitch, that the lack of context given about the works meant we became voyeurs popping in and out of the 13 white boxes like it was a freak show. The poetic and political was lost to the spectacle.

Also, the ‘coincidence’ that when I visited the exhibition each of the works involving women had the performers passive—often nude—and in those involving men, the performers were active. I went to the catalogue—the last hope—to find essays by four men and no women’s voices. But that was just a coincidence too so it’s cool. Lazy curatorial non-decisions left a bad aftertaste.

And (last one, I promise) what a slap in the face that the opportunity to contextualise Australian performance practice in this canon of significant international works from the last thirty years was used to show work by the very early career Clark Beaumont duo (not that their work isn’t strong and interesting—which is beside the point) rather than acknowledge the key works of this mode from recent Australian art history—Rrap, Parr, Stelarc …

13 Rooms, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Pier 2/3, Sydney, 11–21 April 2013.

Work out, MCA, Sydney, 22–28 April 2013.

Thanks to Ash Kilmartin and Eliza Dyball.