Modern zombies

What is it about zombie paint? Or this show at Arndt in particular? Sure, it’s the cool, distanced abstraction that has come to epitomise New York influences, especially the way they’ve revived the big 9’x6’ format canvas. Most artists’ work, too, hones down a single, sometimes beautiful, line of thinking.

There is a temporal necessity I respond to. These zombie painters feel like they waste plenty of time, or have plenty of time on their hands. Or maybe it’s that they spend more time talking and thinking about what they might be doing than actually doing what they do. I don’t mind this. There is something healthy and satisfying in environments where there is always a lot of talk.

Zombies are thankfully not team productions either it seems, and by working alone at the end this adds something ‘felt’ and affirming and implies something existent and in the world with you. These artists propose material physical weight, even as this accentuates the thinner repetitive history of what they are doing, so the double effect carries a sense of pointedness and willingness but is still actually an open breath.

Yet some of the propositions (paintings) were so slim as to be simply daft. It kills me they can get away with it.

Needless this revival of ‘the big 9’x6’format’ has another correlation of sorts in an exhibition down the road at the NTU CCA Singapore.

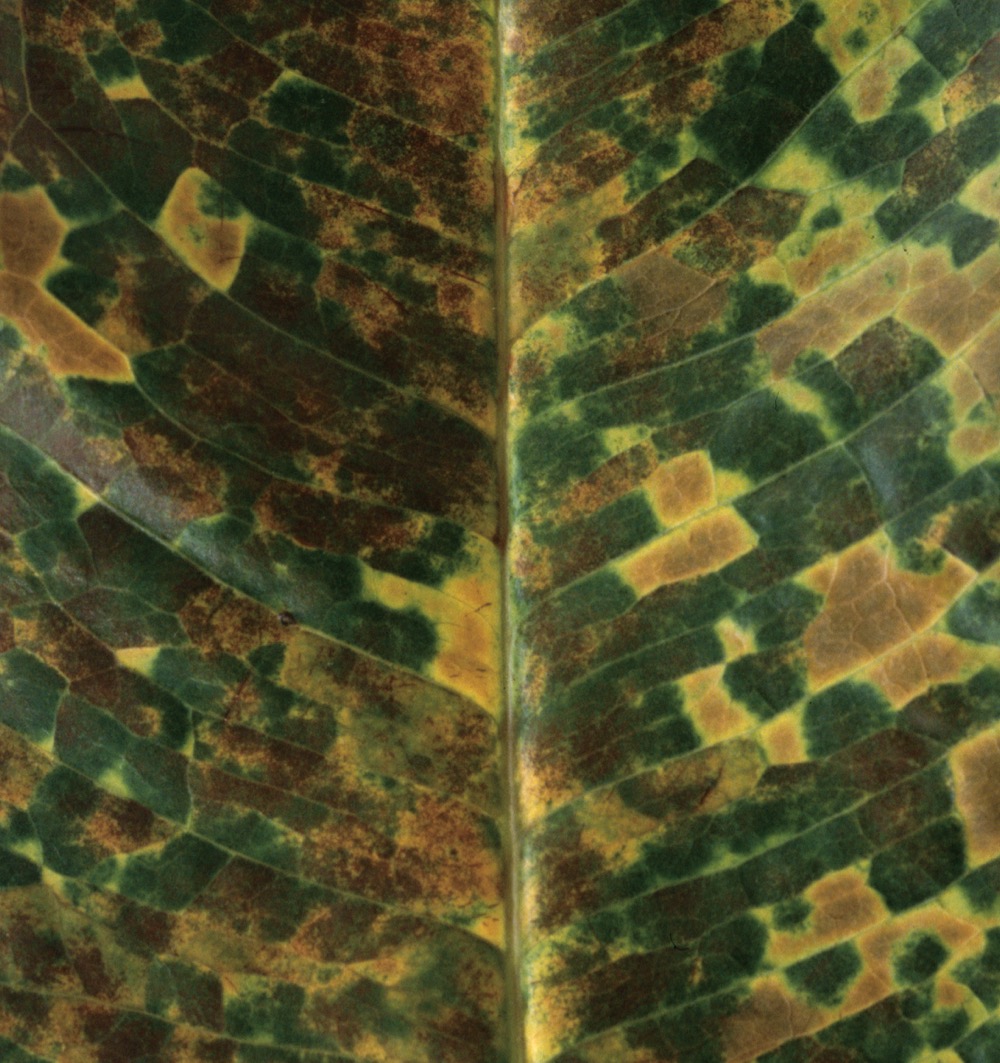

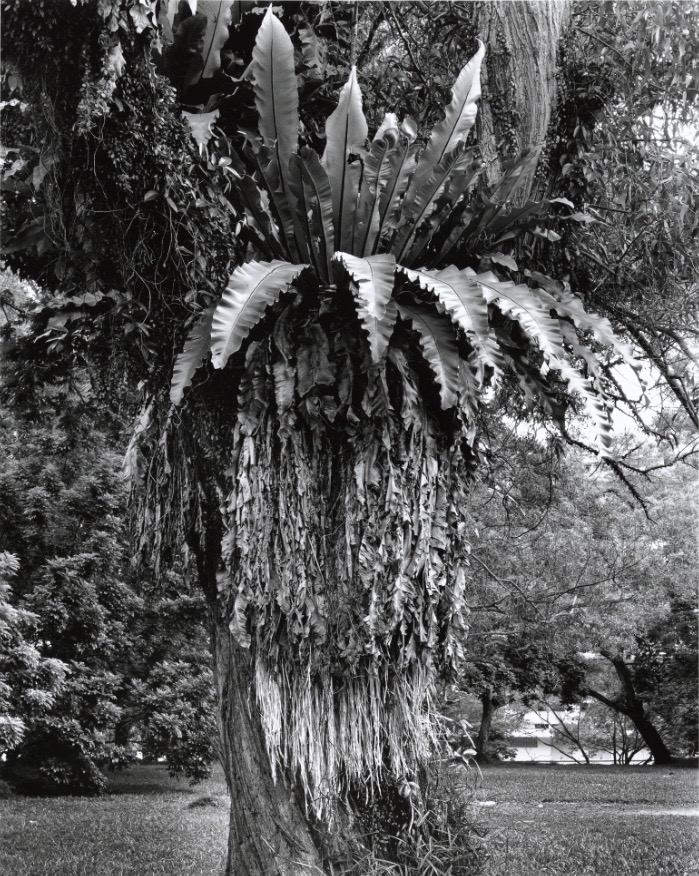

Simryn Gill’s installation of grids of square photographs along monolithic walls draws a straight line with conceptual/minimal tactics of the 60s and 70s. There are no interferences, or spatial slang or wandering at all. Photographs of Malaysian living-room interiors, decaying unfinished building sites and dissected tropical leaves are presented in serried mono-pattern.

It’s a strange installation: a confluence of authority and critique that comes across as slightly acerbic, or astringent. The actual spaces and experience that Gill reads colloquially via the photographs are attenuated up against the ambivalent effect of hard grid formations and monumental walls — possibly here is a point, I can’t be sure.

The sense of existent emptiness and distance comes with an awareness of the contemporary art gallery. Gill’s practice looks to a certain feasibility in this. The exhibition is a collision of place and space. Gill fends off any suggestion of seeking solace or further clarity in specific pictures, or thinking one might inevitably ‘get closer’. Like she says, it might be a matter of hugging the shoreline.

Simryn Gill, Hugging the Shore, NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, 27 March – 21 June.

I Know You Got Soul (Phoebe Collins-James, Liam Everett, Amy Feldman, JPW3, Kika Karadi, Hugo McCloud, Joshua Nathanson, Alex Ruthner, Diego Singh, Marianne Vitale and Jeff Zilm), Arndt, Singapore, 19 April — 21 June.