The what and the why: Berlinde De Bruyckere

I once ordered an exhibition catalogue from overseas. It came in a brown paper package, beautifully bound, with a 10 x 8 cm image of each represented artist’s work. I lent it and lost it. I remember only one image from that book: a distended headless horse-ness. I saw a preview for Berlinde De Bruyckere’s show at ACCA and had to go.

It was a hazy recollection of a very small image and it did not prepare me for the vastness of scale when I walked into the exhibition space. Not even the ACCA publicity shots captured it. Headless horses merged together and hung. One (hind) leg tethered, the way they do in slaughter-houses apparently, to bleed the animals, ensuring tender meat. The work awed and overwhelmed me.

I went to the show with two students of mine, Therese and Linda. At first they spoke about the what of it. What was it made of? What was the artist thinking? What did it mean? I asked them to consider the why.

Later, another student, David, a former neurophysiologist, was drawn into the conversation. Immediately it was the what of the work that outraged him, or at least directed his moral compass: ‘The work employed intentional shock value and the use of their [the horses’] dead flesh as art was disrespectful to their being’.

I do love a stoush, so I interjected: ‘How much more respect is a leather couch?’.

‘Oh, but that’s functional.’

And so it continued. The neurophysiologist related how, as a research scientist, he had used animals, ‘but their deaths were for a purpose’.

‘Is art not for a purpose?’ I continued, teasingly.

Therese interjected: ‘Could it be that [David] had not reconciled himself to particular aspects of the work [he] had undertaken as a research scientist?’.

‘Perhaps that is true’, David admitted.

Next we all went along to the ‘On flesh’ discussion, one of the public programs that accompanied the show.

Among the panel members was a meat scientist from the CSIRO. We were informed that ‘slaughter-house’ is not the correct term when referring to a slaughter-house. It is properly called a ‘processing plant’. Of course.

An embalmer offered that we should learn to embrace death. He was good-humoured and compassionate. He had made black shiny maracas with his grandparents’ ‘cremains’.

There was a professor of film, and a psychologist with expertise in disgust. The psychologist spoke of cognitive dissonance. Finally, there was a chef and meat merchant, who relished meat. He was the only one on the panel who had killed an animal (with his father at age six), to learn where meat came from.

Afterward we had dinner at Cookie. The pork belly was excellent. Inspired or inflamed, our conversation went from Victorian England—serfs and landowners—to politicians and rulers and the countless soldiers sent to wars around the world.

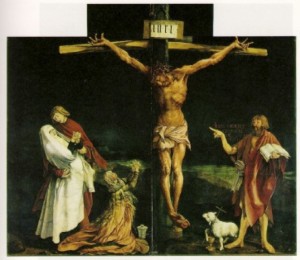

I thought of Grünewald’s depiction of the crucifixion, how an image of torture and a depiction of death and suffering becomes an image of reverence and humility.

I think I thought of the why.

Berlinde De Bruyckere, We are all flesh, ACCA, Melbourne, 2 June – 29 July 2012.