Matt Hinkley bumps and sprained ankles

A few months ago I sprained my ankle. I kept checking it, to see how it was swelling and discolouring. As the day wore on, I saw it grow to the size of a separate appendage, bulging out from the normal line of my ankle. The flesh became tighter, like a sausage about to burst, and as time passed the colour changed to a mottled darker pink, which then slowly flushed out a diseased looking yellow blush.

That day, I went to see my sister and her kids. They were bored and I said, “I have something to show you,” and peeled away my sock, not really expecting much, but giving it a try. My 3 year old niece, who really loves pink, peered at my sausage ankle and said, “I like it like that.” She seemed interested in the way my ankle had morphed into a recognizable but exaggerated version of its natural state. Both she and her brother kept circling around my ankle, wanting me to show it to them again and again. In its hyper state, it seemed to become bigger than life, magnetic.

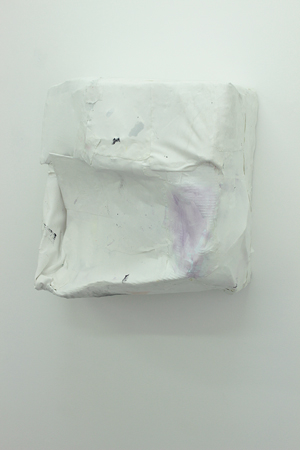

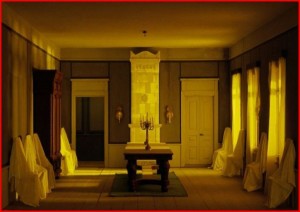

In The Mechanic, at Neon Parc, Matt Hinkley was showing Untitled, a cast sculptural form. As a hanging sculpture closely attached to the wall, its bulbous expanded shape drew me in. The white surface blushed with the occasional discolouration, not of a bruise, but a topological flushing out. I kept peering closely, looking in and around it, drawn to the awkward curves and bumps. As I peered in, the surface breaks appeared low like a goose-bump, but possibly so small I downsized the scale to a freckle – so small that your fingertips might not be able to discern the raising in the flesh, so you would have to use the back of your hand to run over it for sensation, and pick up the way these indentations deckled the surface.

I feel like I sprained my ankle because I was flat-footed. My ankle didn’t hold me up: it collapsed and hugged the ground.

Maybe a collapsing ankle has greater and closer contact to another surface, and so has a friendlier relationship to its environment, like Matt Hinkley’s work. And I like it like that.

The Mechanic, Neon Parc, Melbourne, 29 April 2015 – 30 May 2015.