Things I learned from ‘The Diplomat, the Artist and the Suit’, a documentary about architecture firm Denton Corker Marshall

1.

In the competitive field of architecture, three things are essential to success: The first is a level of diplomacy, required in the courtship and management of clients. The second is a high degree of artistry or design skill, indispensable for obvious reasons. The third is a suit. Many budding architects, in their hubris, neglect to acquire a suit. This is a mistake, for no level of artistic talent or interpersonal and management skills will compensate for deficiency of suit. The more ambitious will invest in a second suit, so as not to be without when the first is being dry-cleaned. However, when starting out, it isn’t necessary to purchase more than one suit. Seven is excessive.

2.

Barrie Marshall is the artist of the documentary’s title, a self-effacing, wiry-framed recluse with glassy brown eyes. I want to make love to him.

3.

Marshall lives in a concrete bunker resembling the HQ of a horribly disfigured cartoon villain with chainsaws for hands, sunk into a dune on the rugged Phillip Island coast. Its entrance is marked with a galvanized metal screen, its interior ruthlessly austere and as cold as the Bass Strait winds. There is a large enclosed courtyard, covered in dune grass. There are no penguins.

4.

In the history of vox pops (and probably since Neolithic times), no member of the pubic quizzed on the subject of new architecture in their city has had a single positive word to say.

5.

I bet he goes walking alone on Woolamai Beach in the driving rain, his mind harboring melancholic designs and secrets and a longing for the freedom of a sea bird.

6.

Jeff Kennett is the Lleyton Hewitt of Victorian public life. Now that our white-hot hatred has waned, the former premier’s/tennis champion’s comments are sought on the immaturity of community attitudes to public space development/Nick Kyrigos. Since retiring from office, Kennett may have done much to raise awareness of depression and anxiety but there is still a cactus where his heart should be and he still thinks we’re a bunch of lowlifes.

7.

Anyone who doesn’t like the DCM-designed cheese stick on Citylink is an idiot and should aspire to a higher level of architectural intelligence.

8.

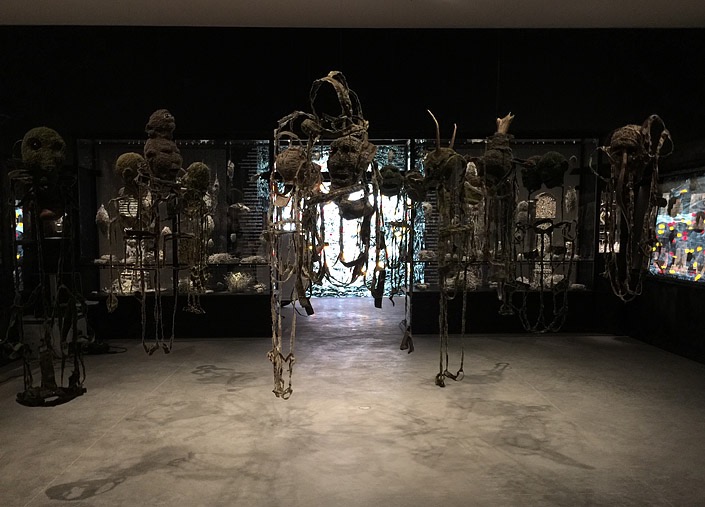

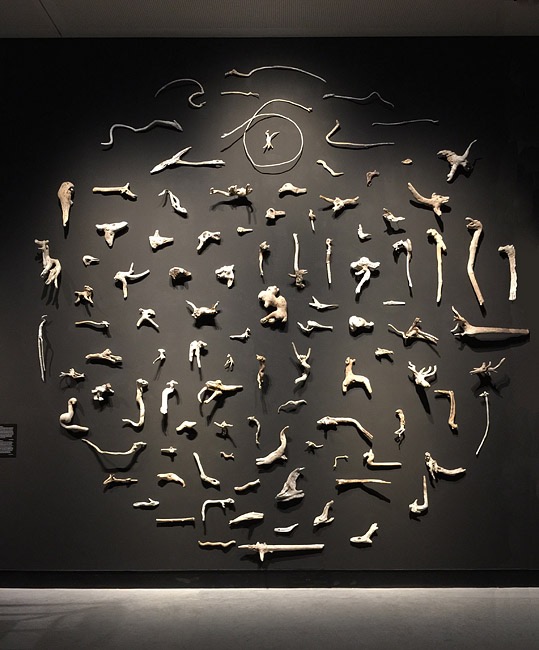

Anna Schwartz lives in a DCM-designed home in Carlton with her husband Morry and a world-class collection of contemporary trip hazards. Also, she has retired the reflective hat that made her look like a Parisian gumnut baby.

9.

Across a range of factors—environmental sustainability, structural complexity, number and accessibility of public toilets—the DCM-designed Stonehenge visitor centre is, compared to the Stonehenge itself, the superior achievement.

10.

I doubt I’d actually make love to him if given the chance. His bed is probably made of zinc. What would we talk about afterwards? I‘d have to pretend to like the cheese stick.