Pirate – bug – museum

An unspectacular football match between Steaua Bucharest and the Norwegian team Rosenborg Ballklub which took place last week made me realise that ten years ago, almost to the day, these same two teams had met with the same result (Steaua losing to Rosenborg). The entire situation, together with the chronological coincidence, made me recall an exhibition with an unusual format, presented only for a day, on the 23rd of August 2005.

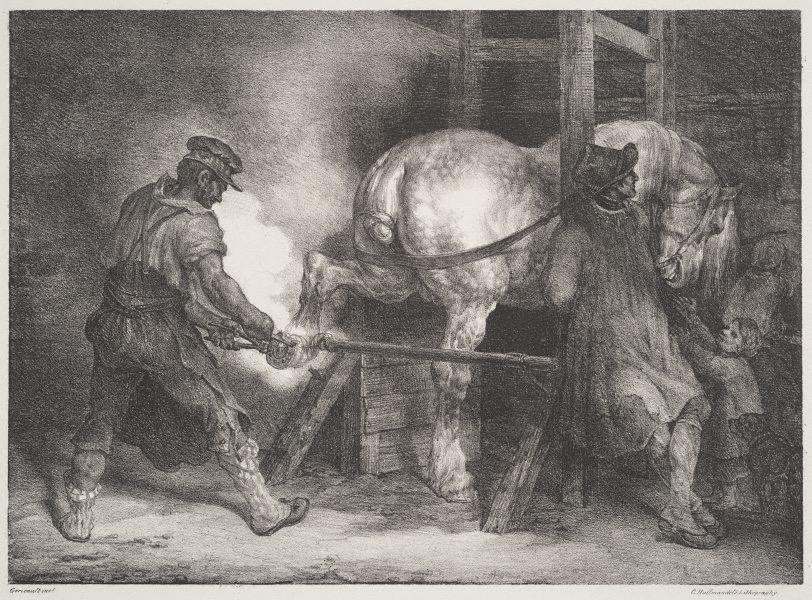

Liviana Dan is a curator whose work dates back to the ‘80s, with ‘uncomfortable’ projects in various space-formats, from basements and streets to exhibition halls in a number of Romanian cities, with a particular focus on Sibiu – a medieval city situated in central Romania. Back in 2005, Dan initiated a curatorial direction in the museum where she was working: An Artist – A Day in the Brukenthal Museum. Situated in Sibiu, the Brukenthal Museum is one of the oldest museums in Europe, opened to the public as a private institution in 1817 (although there was notable public activity in the collection long prior to that date).

An Artist – A Day in the Brukenthal Museum had a genuine laboratory structure, testing whether young artists could wield the complex structure of an old art institution and discover its soft underbelly. It was not about assailing what the museum represents, but rather about unveiling its vulnerable or unseen sides. The invited artists were supposed to make a one-day intervention in one part of the museum, without disrupting the usual display, but still questioning the history of art as a “sequence of successful transgressions”, to quote Susan Sontag.

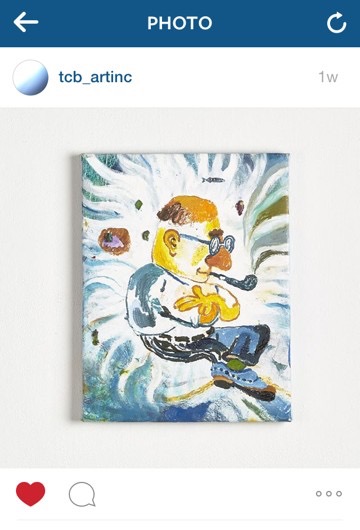

The exhibition that day was entitled Almost Censored and it featured a site-specific installation conceived by Sebastian Moldovan. Freshly out of art school, the artist was rejecting the academic system, and the museum-as-exhibition space was too much. In this state of in-betweenness, he chose to work with that standard silence each museum encompasses, and explored the condition of closed systems or circuits that can’t support any charge. These days, when asked about the exhibition, Sebastian recalls that he could feel the museum was a serious institution and he acted like a sort of ‘pirate’.

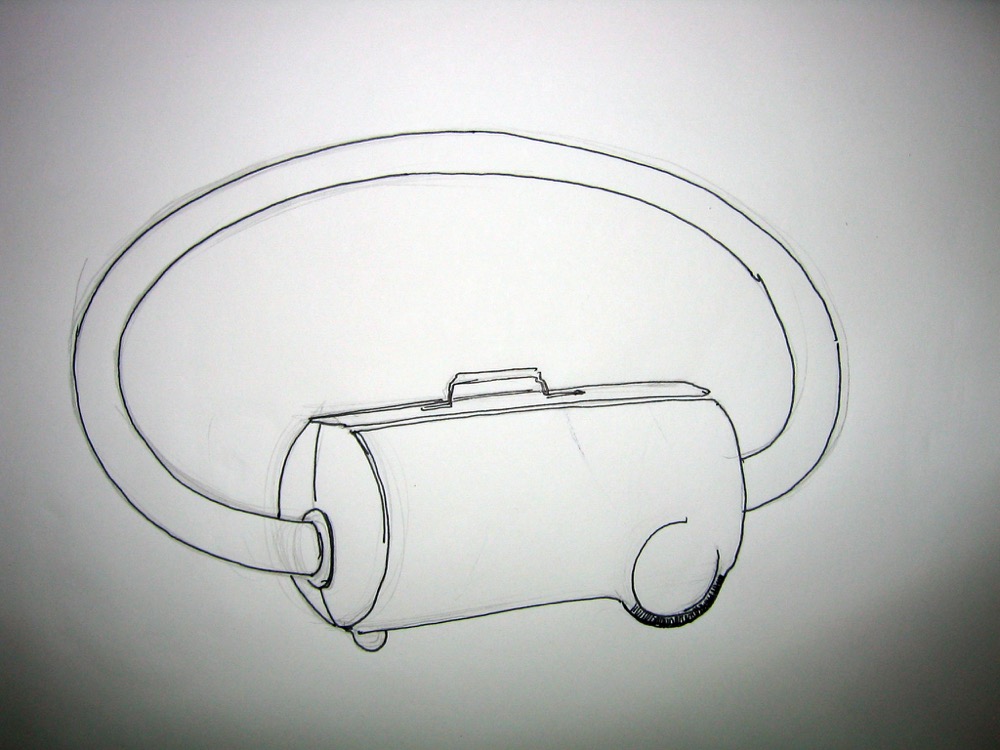

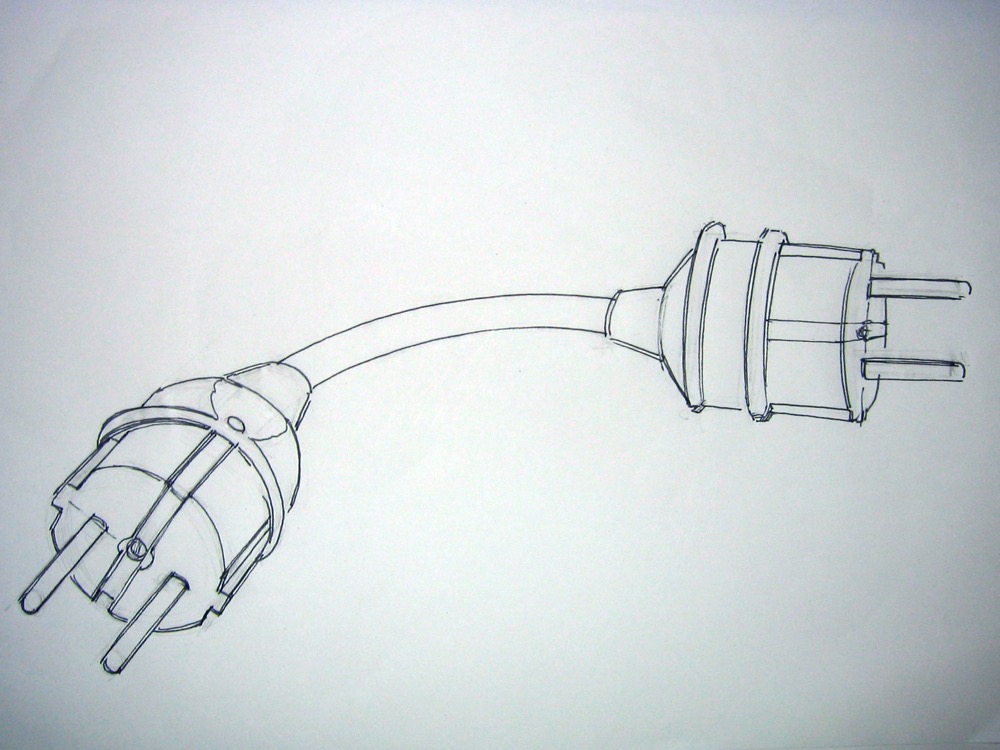

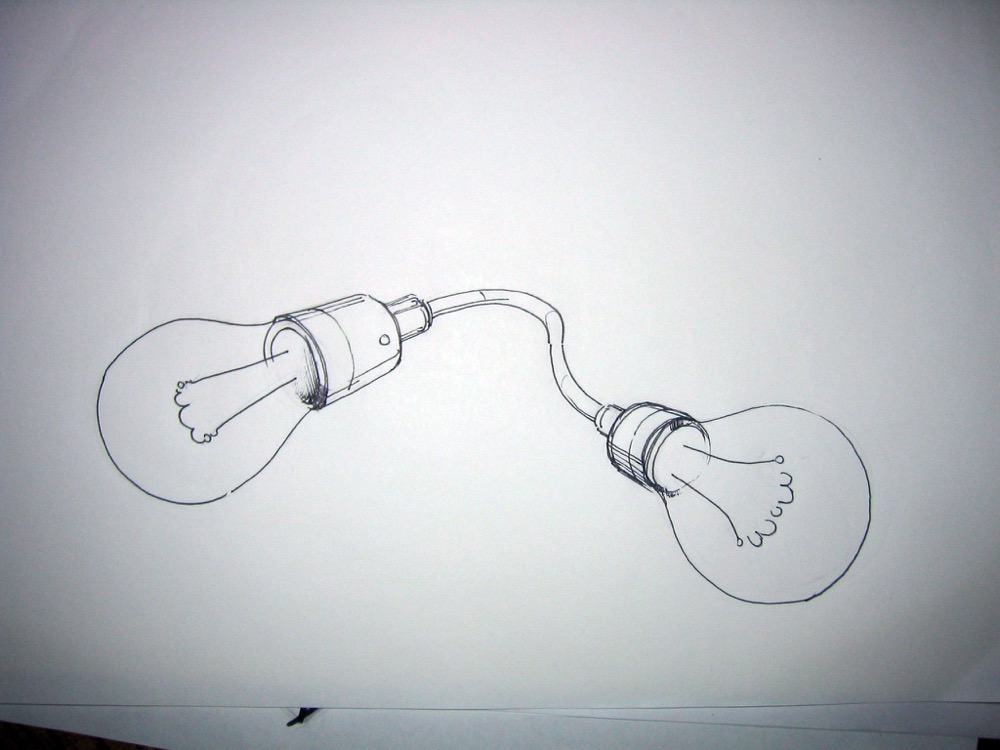

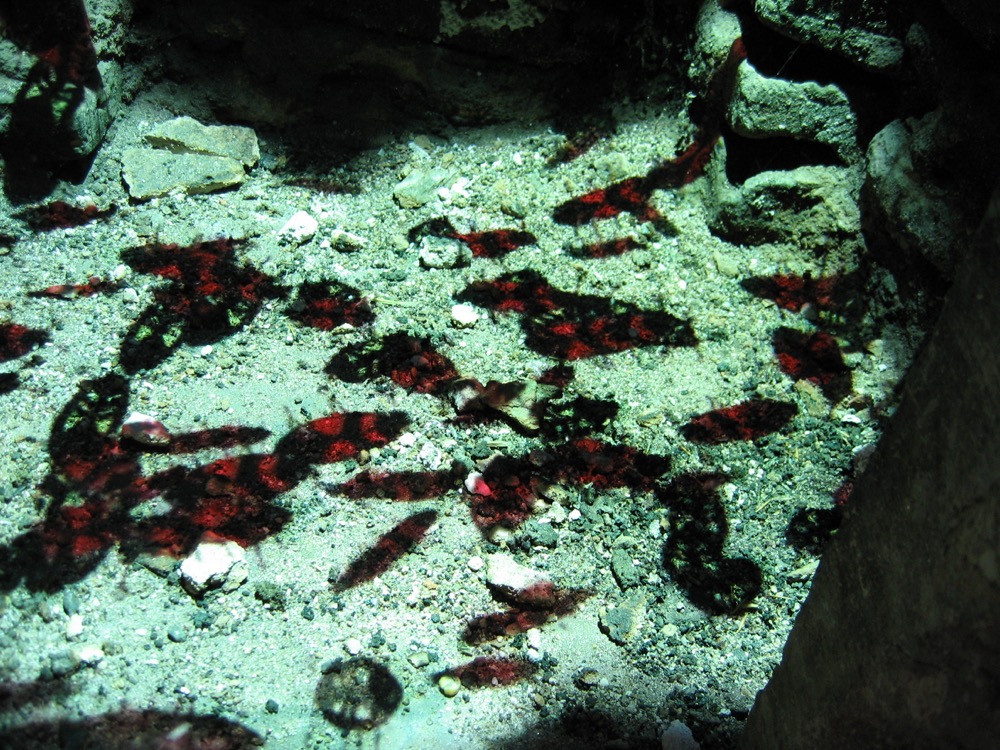

There was one video installation installed in a former chimney ( the space where he displayed his works had functioned as a kitchen in the past) showing various animated bugs walking around the dust that had accumulated at the bottom of the structure over the years. The work was playful and earnest at the same time, being supposedly about the bugs that walk under the skin of the museum. The other elements featured in the installation were two conjoined vacuum cleaners wrapped around a pillar, two bulbs and two plugs connected to each other, and a popular metal hook destined to keep a door shut: simple statements about the state of things, without much mystification.