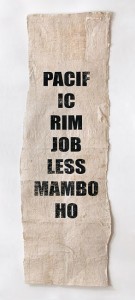

Prince screws

About a year ago I read the collection of essays, Pulphead, by the American magazine writer John Jeremiah Sullivan. I’d seen his work here and there, and knew he was good, but a collection presents the opportunity to see where the piecemeal work of a pen-for-hire might add up to something larger.

There are brilliant essays in Pulphead, and some not so brilliant, even one or two fillers. An essay on Bunny Wailer originally published in GQ is a standout. So too is Mr Lytle, Sullivan’s memoir of his eccentric early-career benefactor. Thinking about Sullivan’s writing now, and other writing like it, I realise a lot of it comes down to the treatment of character. Because he rarely takes the expected position, the people Sullivan profiles emerge as far more complicated than they otherwise might. The terms of engagement are reset, which seems especially meaningful for those figures who would elsewhere be easily pilloried.

The old adage goes that a certain kind of writer always betrays someone. They draw close to a subject, build something resembling trust, and then disclose as they see fit. But more than that, they map the narrative points and then argue the veracity of the lines they plot between them. This is, of course, a deeply subjective undertaking: if the points are interchangeable, shifting from every perspective, then the lines too can easily shift. But if the position a writer takes is fresh enough, and their argument compelling, then it just might change the way you think. One measure of good writing, then, might be that it never quite settles. There’s always the hazy uncertainty that what you are reading is still in play. There’s a risk to it.

What we do in the art world is usually a bit different. We don’t generally do character, for one. Plus the writer’s remit – whether they be curator, critic, or historian – too often cuts the grey ground between advocacy and advertorial, with neither form well suited to big risk, or unexpected disclosure. Read a catalogue essay and you usually get what you expect; same goes for a scholarly essay, even a review.

But this isn’t always the case. The other day a friend forwarded me a recent review by the British art historian Claire Bishop. At a glance it might not seem out of the ordinary, but it pushes back against the kind of collective non-thinking that can at times seem to thread through the writing that the art world generates. Bishop argues not only for a critical reappraisal of a widely celebrated artist, but also thinks harder than most about the proliferation of artist-as-curator projects.

Neither are fashionable positions, but on both accounts her argument is timely (rather than simply of its time). It’s an example of a writer shaping the discourse, rather than simply perpetuating it.

There’s something at stake in this approach. Whether you agree with the writer’s position or not, the sense of risk pulls the reader through. All of this sounds serious, but it can be revelatory too, playful even.

Sullivan, fascinated by the human scale story (even when writing on characters whose very existence seems to buck the whole notion of human scale), plays this position well. Take the following passage from the essay Michael. Not only does it deftly restage an overly familiar figure at a key moment, it shines new light on a prejudice about its subject that we pretty much all unthinkingly hold: that his was the special order of craziness reserved for extreme celebrity, and thus unbounded by history. In a few simple paragraphs, the conversation becomes about something else entirely:

Prince Screws was an Alabama cotton plantation slave who became a tenant farmer after the civil war, likely on his former master’s land. His son, Prince Screws, Jr., bought a small farm. And that man’s son, Prince Screws III, left home for Indiana, where he found work as a Pullman porter, part of the exodus of southern blacks to the northern industrial cities.

There came a disruption in the line. This last Prince Screws, the one who went north, would have no sons. He had two daughters, Kattie and Hattie. Kattie gave birth to ten children, the eighth a boy, Michael – who would name his sons Prince, to honor his mother, whom he adored, and to signal a restoration. So the ridiculous moniker given by a white man to his black slave, the way you might name a dog, was bestowed by a black king upon his pale-skinned sons and heirs.

We took the name for an affectation and mocked it.