Fine family living

‘Australia’s is a special kind of philistinism, an immovable materialism which puts art and ideas of any kind deliberately and firmly to one side to let the serious business of living proceed without distraction.’ Robin Boyd

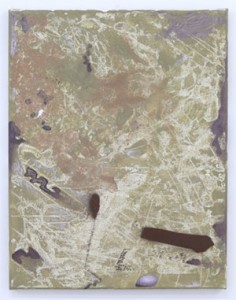

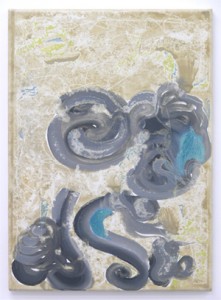

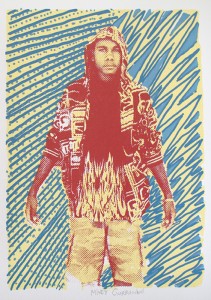

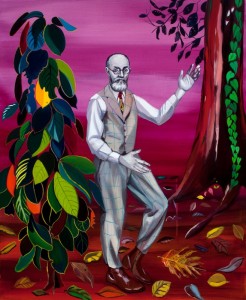

Just to the side of the city Matlok Griffiths rides back and forth from Richmond to his studio at the Abbotsford Convent. In his spare time between his job as a graphic designer and his study to be a high-school art teacher, Matlok slips off his Melbourne attire and slips on a pair of long shorts and paint-spattered T-shirt. He might then water the mother-in-law’s tongue succulents that line his small window overlooking Collingwood and fire up the air compressor air as he sprays, sands and slaps paint down on a board or large canvas. The starting point for a painting is usually something domestic: fruit or pot plants or something graphic like the Lacoste crocodiles who popped up everywhere on his recent trip to Cambodia. A hand of bananas, black and shriveled, sits atop his small red tape player. These charred models are resuscitated in paintings with a jazzy array of acrylic and spray-paint colour. Shapes and marks are made and Matlok might scratch his head, leave and have a soy chai before heading back to completely rub away all his work for something new to appear. It seems right when it’s wrong. When it’s allowed to be wrong all sorts of doors may open. As the sun sets in the east over Carlton an array of Philip Guston nobby type characters and cartoony figures and shapes all emerge for a party in this little nun’s bedroom, all feeding off the wholegrain rice crackers and hummus kept on the shelf.

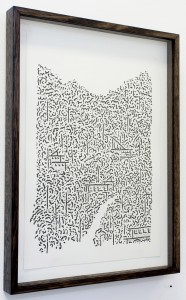

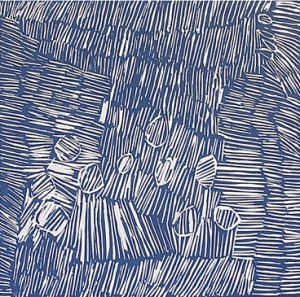

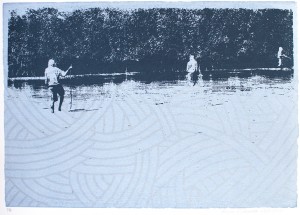

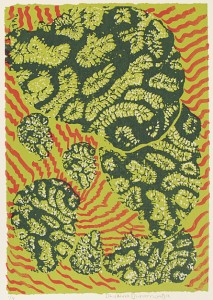

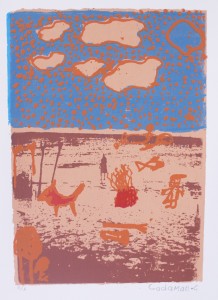

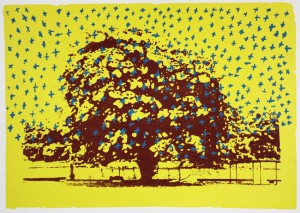

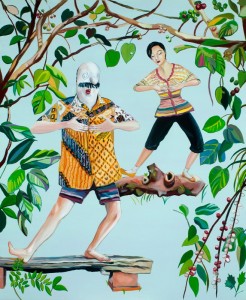

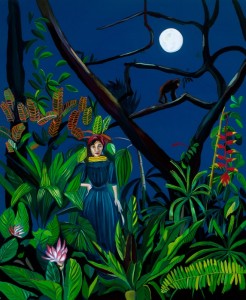

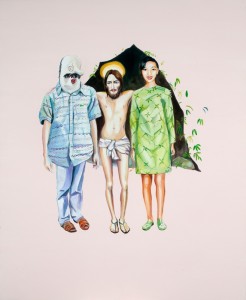

This month Matlok exhibits with four friends who rarely show their art, all a little shy to enter the smelly art stage. Hank Josefsson from Scandinavia, Julia McFarlane, and Rick Milovanonic, musical members of the Twerps. Individually they each made a painting around the theme of ‘fine family living’. The next painting was then made using an element from the last painting. So you get very playful variations on the theme as the language of each artist’s work is digested and then reworked. The finished result is a fresh little show. Hank’s Scandi background and painterly flare give different perspectives and angles all on the one picture plane creating work as one might imagine a very small David Hockney might. Julia’s prints are flat and objects are reduced to shapes and colour. They take a close-up look at architecture and garden features as if walking around a backyard. Rick translates various patterns and features into black and white prints, the lovely reduction and neatness of modernist architecture buzzes with the plant patterns and house angles all singing together.

Hank Josefsson, Julia McFarlane, Matlok Griffiths, Rick Milovanovic, Fine family living, St Heliers Street Store and Gallery, Abbotsford Convent, Melbourne, 1–16 September 2012.