Secret art places: Part II

Cetate Arts Danube, the other art-camp I visited in August, has been situated since 2008 on the same premises as the one in Tescani, but the methods of work are somewhat different. Initiated and supported by the Joana Grevers Foundation in Bucharest, the art-camp in Cetate is hosted in a mansion built between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century by a local landlord, Barbu Drugă. It is a beautiful Art Deco building, with Mediterranean influences.

Ştefan Creţu (RO), Simon Iurino (IT/ AT), Cristian Răduţă (RO), and Napoleon Tiron (RO) were the four artists invited to create new artworks in Cetate last summer. Over the years, all the invited artists have colonised the available spaces with their art: the old barn has taken the function of a Kunsthalle, while the vast area surrounding the buildings contains artistic interventions that surprise the viewer, especially in connection with the architecture of the place.

Napoleon Tiron, an iconic Romanian sculptor now in his eighties, placed a monumental sculpture of multiple spread wings in the garden of the mansion. For days, he cut and calculated dimensions, researching the area in order to find a position for his structure. At the time of the residence in Cetate, Napoleon had been reading about the history of landscape, van Gogh’s letters to his brother and various biographies of artists and musicians, and these writings inspired him to closely listen to nature and the sounds people were making.

Not far from Napoleon’s work, Cristian Răduţă placed a tree-shaped stand decorated with coloured plastic plates he had bought from the local market. He was calling this construction “a utility tree”, and it represented a major change in his practice, as Cristian had previously been oriented towards large-format sculptures, usually using different resins, which were bound to the studio, without exploring or interacting that much with the surroundings.

Ştefan Creţu, one of the artists that had been coming to the mansion for several years, sought inspiration for his kinetic sculptures in Darwinism. His main interest is following the evolution of humanity from amphibian to machine, stressing the limits of artificial intelligence.

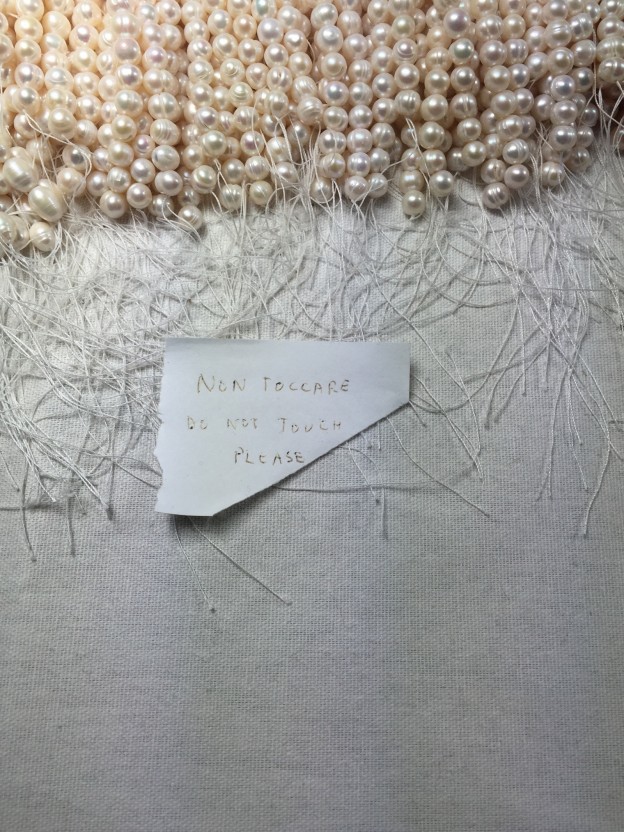

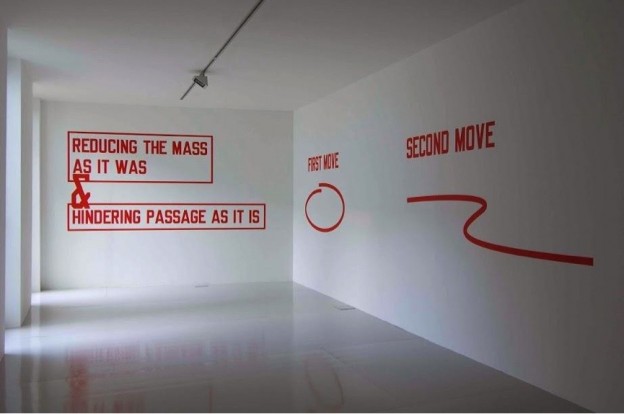

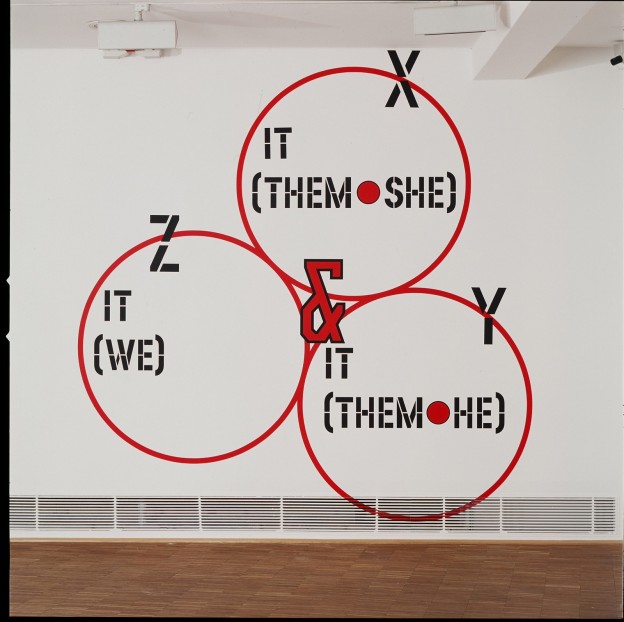

Simon Iurino was focused on utilising materials from existing structures, working with the plan of the space, appropriating their context and analysing the function that these old objects had before. The series of cyanotypes he produced at Cetate were describing fragments of architectural details, combining the textile with the text and its form, in an attempt to test the expansion of linguistics.

While wondering about the local mythology in the remote village of Cetate, I unexpectedly met the British writer Selma Dabbagh who joined us for dinner one evening. She was writer-in-residence at Port Cultural Cetate, the old agricultural port by the Danube, once part of the Barbu Drugă’s estate and transformed in recent years into a cultural centre by the Romanian dissident poet Mircea Dinescu.

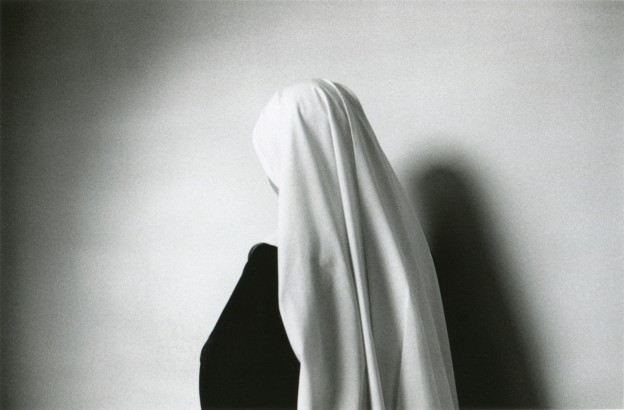

Selma had been talking to the local people, taking notes on mysterious situations and exploring stories told by the villagers while they were pursuing their daily errands. The night we met, during the time we were visiting the cellars of the mansion, Selma mentioned a very interesting story about a young woman turning old upon her death. The story somehow brought me closer to the intimate strata of the community, surrounded by borders – the first border being the Danube, from where one can spot the second and the third borders with Bulgaria and Serbia.

As I noted at the beginning of the text, the combination of the shock of the image, the human condition and the thin line between past, present and future define the spaces that assume a position outside the standardised art system.

And here is the story told by Selma:

The woman who serves us waves her hands around. I understand nothing of what she says. I am the only person in Port Cetate who does not speak fluent Romanian. There are many things I still don’t understand about Romania, but at least I have learnt not to mention Dracula. Port Cetate, on the Danube in the west of Romania, where I am writer-in-residence for a fortnight, has set up a sculpture park of angels to counter the Dracula park project being mooted for Transylvania, a region in the north of the country. There is indignation in the look of the woman serving us, possibly at not being deemed credible; that much I can comprehend from her challenging eyes. I like this serving woman. She bounds from table to table, talks in a flurry and has no time for anyone. She’s like an Almodovar woman without the legs, high-heels or subtitles.

What is she saying?

They’ll tell me. It’s a long story. A big story. It has been going on all week. But interpreters are fallible. If their curiosity does not match yours, you end up with holes in your tale, gaps that can only be sewn together by fictions.

First they tell me this:

There had been a death. A woman. A mother of six children in the local village, Cetate, where all the workers came from. This woman, a relative of many who worked in the kitchen, had fallen in the road, was taken to the hospital and died in childbirth. The baby was fine.

I couldn’t get this at all.

Tragic? Yes.

Deserving of the facial expressions and daily updates? No.

Could someone explain further please?

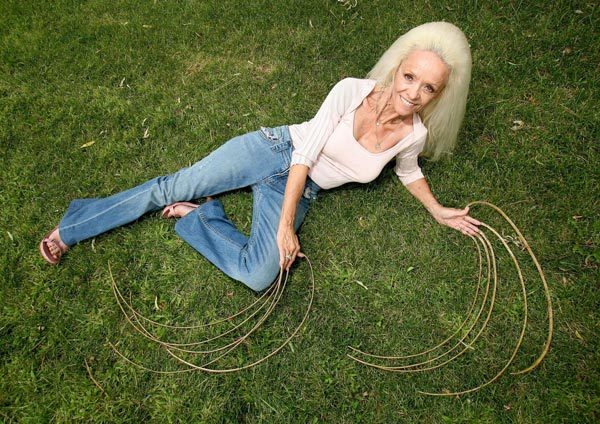

The thing, they explained, was the body. The body of the woman had aged. When they went to bury this woman in her thirties, they found an old woman. She looked at least 70 in the open coffin.

What else? Surely there was more.

They now felt she was haunting them. She had scared them. They could still see her. She never went to the hospital to give birth. She never would have been in the hospital if she had not collapsed. There had been many other children – that was the other thing – maybe as many as 22. The others were born and buried in the woods. Only a handful survived. That’s why they feared her. That’s why she couldn’t rest.

On my last Saturday I am taken to one of the workers’ houses in Cetate for a barbecue. We open the wine by pushing the cork in after banging its bottom against the rough stucco wall of the house. I eat a spicy sausage sitting on a blue plastic stool and am handed a litre of rosé in a tankard. A mobile phone is propped up in an empty beer glass to play us some music as we sit. There’s chat. Someone hands me a phone with a photograph displayed: a baby in a blue and white onesie lying on a towel. The child, it is explained, is the boy of the woman who died.

He’s being baptised the next day. Isn’t he cute? I consider the wriggling infant trapped in the tiny screen: a child known from birth as the progeny of an infanticidal witch.

Angelic, I reply, slipping the phone back into the glass for the music to continue.