Atlas: Andrew Hurle

Andrew Hurle’s work in Post-planning is about human imagination and its roots in pathology. There are six artworks: four small constructions (models), some more unfinished looking than others, and two prints about A3 size and pinned.

The works are installed as a group on a stage or rostrum built of black stained timber sheets—a display device designed by the curator and a consultant architect. The stage mimics some of the material effects you notice elsewhere in Post-planning but as well blurs the edges of where the artist’s work finishes.

Each of Hurle’s works takes as a lead his recent research into economic and banking systems. He describes this as ‘the subject of counterfeit, the psychology of wealth and the various anxieties that formulate in prosperity’s shadow—such as loss, theft and bankruptcy’.

The titles give an indication—there’s a wedged replica inkjet Postbank headquarters, Hellesches Ufer 60, 10963 Kreuzberg, Berlin for instance, and One Chase Manhattan Plaza, NY reminds me of Thomas Schütte’s Basement sculptures circa 1993. The most intriguing works perhaps are the two plainly exquisite inkjet prints pinned to the backboard and titled Guthaben (Ghost account), 2011. Hurle has lifted somehow and replicated page blanks from Nazi bank passbooks used by Jewish inmates in concentration camps.

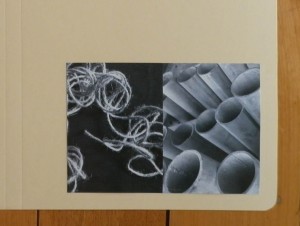

What I like about Hurle’s interest in modelling is that it’s not confused with crafting or used as a vehicle for generational pathos. His sculptural models are still in large part schematic, closer to actual architectural models in their making and proportions. What is different is how Hurle incorporates his complex understandings of 2D printing technologies into the designs. You might argue these ‘models’ are actually 3D images.

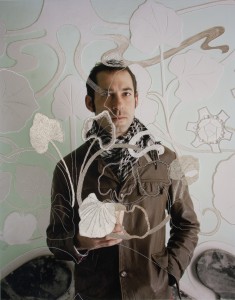

Hurle is a printing specialist and as such has a very heterogeneous and gregarious curiosity about images and image reproduction. His image awareness is like an atlas. Images are a place and point of orientation as well as promising forms of knowledge. In Post-planning Hurle is particularly focused on images that are pernicious or rendered speechless or are aphasic.

Andrew Hurle, various works, Post-planning: Damiano Bertoli, Julian Hooper, Andrew Hurle, Alex Martinis Roe, Michelle Nikou, Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 31 March – 22 July 2012.