How to quieten the mind

Lately my brain has been full of the effects of change and heat and nervous anticipation, and even in the quiet moments it is hard to find even a minute or two of contemplation from which an original thought or opinion might form itself into something worth spinning into the outside world. The last thing anyone needs is yet another mediocre observation from a brain full of scattered and racing thoughts.

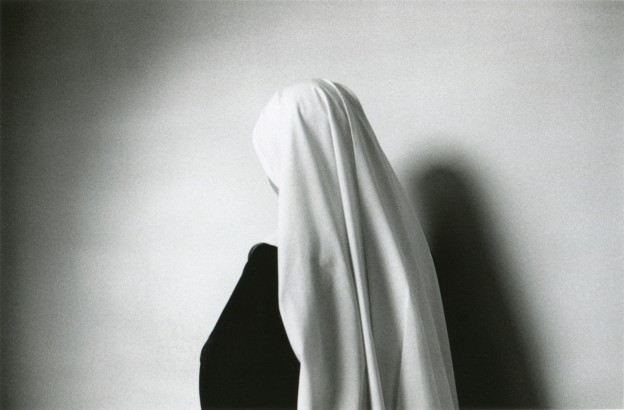

When the present becomes too close to bear like this, the past comes into sharper focus. From this swirling mire of idea-less exhaustion came a memory of a first encounter with a work that really struck me as remarkable and true. Anne Noble’s The white veil of a novice “Our habit signifies complete detachment from the things of this world” is a black and white photograph from a series taken while in residence with Benedictine nuns in a London convent from 1988-90. It’s a portrait of a young nun, but also a mysterious study of light and form. The veil and its folds sit at the centre of this small work, which is barely 20 centimetres wide; a tiny sliver of the side of a face can also be seen. The drape of the folds is determined by the curve of the novice’s head, as still as marble. A dark shadow and an equally dark habit are voids against which the white veil sits. The wall is blank; a shadow settles across its left side. Its subject is thoroughly self-contained.

My memory is that I first saw this photo in a gallery in an old house on a hill in Auckland that is no longer there, but I can find no record of that now. Maybe we make memories to comfort ourselves. Either way, I would love to be sitting in front of it in that real or imagined place now.