Like seeks like

I enjoy the kinds of informal connections that you can make by simply looking at different artworks. Sometimes the brain has to catch up to the eye and try to explain away coincidences, or alternatively make a case for initial and perhaps superficial visual similarities to become more than that. It’s always positive to begin to think about the world view embodied in artworks, and for this to help you face down preconceptions about how things should or shouldn’t be. After all, what good is an artwork that simply reinforces the way you already see things?

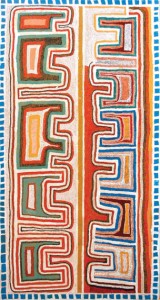

Recently, while at the NGA in Canberra, I visited a work I like a great deal: Boxer Milner’s Milnga-Milnga, the artist’s birthplace, 1999. Someone talked to me about Milner’s work a few years ago, emphasising that once you get an understanding of his pictures they begin to work on you, but first you have to ‘get your eye in’. It’s true—before you know it you are really looking at them—thinking about where blocks of colour end, where outline becomes infill and about the multitude of decisions you can read in his pictures. They also raise broader questions about how content relates to these kinds of decisions, and where form might unhinge from an underlying framework of representation.

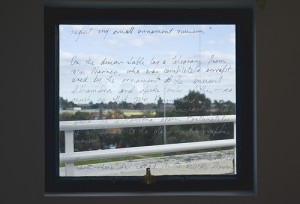

A number of days later I saw Nick Selenitsch’s show at Sutton Gallery. There’s a series of visual coincidences between the artists, but I would suggest that some of what the eye picks up represents more than this, and that connecting one with the other defines a mid-ground that both artists negotiate. Milner’s decision to render the winding paths of drying waterways as a striking geometry presents as a specific ‘painterly’ decision, one that’s about pattern-making and design as much as it is about representing country. Similarly, Selenitsch’s focus on the line markings that define areas of play places a geometric topography on the land’s surface and provides the crux of his work: abstraction’s signification of the real world. Each displays a tendency to adapt specific content away from literal or prosaic representation—frameworks shift and change in relation to the logic of each work.

Drawing these connections is nothing new. Comparison like this has a long (and often misguided) history, especially since Indigenous contemporary art has been established as an undeniable art-world presence. It often raises persistent and unresolved problems, both of categorisation and misrepresentation. But raising these problems makes us consider them more closely and, at an informal level at least, looking at paintings and thinking about what artists do will continue to suggest that practices can and do converge in unintended places.

Nick Selenitsch, Felt, Sutton Gallery, Melbourne, 20 April – 19 May 2012.

Boxer Milner, collection display, the Kimberley, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.