Against nature—Charles Lim and ‘Sea State’

We have a personal bomb shelter in our flat in Singapore; most homes do here. It’s a hard thing to reconcile. In my mind household bomb shelters are something that Hollywood invented via nuclear disaster movies such as The Road. Sure bomb shelters seem a long way from Charles Lim’s Sea State Singapore Pavilion exhibition, but then again it’s possibly a straight line.

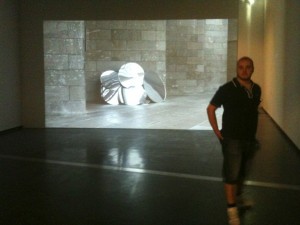

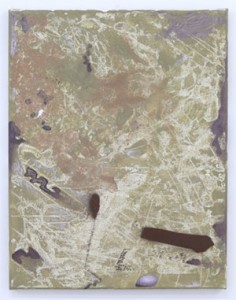

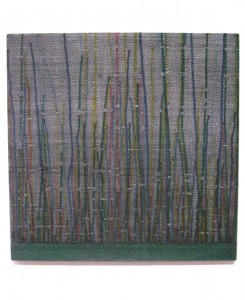

Charles Lim’s artworks in Venice are in the main film and documentary material displaying Singapore’s endless land-reclamation activities and island geo-engineering. Singapore is highly engineered in the same way many newly emergent global cities are. Like other national pavilions though, it’s hard to get at exactly what is at stake.

The last artist I remember who confronted the triumphalism of national pavilions at Venice was Hans Haake in 1993, where he smashed up the Nazi-era German Pavilion. He lifted and broke all the stone flooring leaving it a place of disorder and latent violence, and adorned a photo of Hitler in the portico in remembrance of the visit to the building in 1938 and in the main pavilion wrote ‘GERMANIA’ over the top of it all.

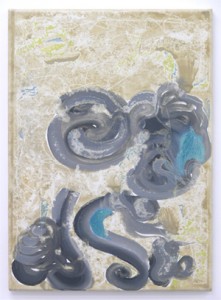

So what about Sea State? Well it’s not smashing anything up. And it’s not anything like a Hans Ulrich Obrist-style ‘post-planning’ zone that is applied to other globalising Asian cities. Sea State by contrast is coherent and shaped. Its ideal is a fluid but dissipated sense of subjectivity. It is not declarative or demonstrative, quite the opposite.

It is a fact that wherever you might dig a hole in Singapore you will invariably come upon broken concrete and tiles, or kampong detritus and what was once foreign dirt. In a slightly double-schizoid way Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, the curator of Sea State, goes quite a way to dissuade intuitions that land-reclamation practices are in some way an unnatural act. In this he is aware of regional sensitivities where land possession arguments are involved but in my mind there is nothing particularly spooky about Sea State, even where Charles Lim twirls the stick a little in drawing attention to Pulau Sajahat translating as ‘Evil Island’.

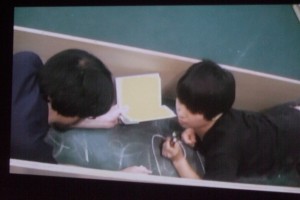

The Sea State aesthetic is in large part cinematic and monumental. It is mesmerising and technologically intoxicating. Charles Lim has an intriguing knack with presentation where he strips away the black cover plastics from commercial screen equipment to leave sheer naked glass and metal.

From an international perspective what stands out with Sea State is the geo-political parallels in the South China Sea. China’s historic sea claims do in fact reach down just north of Singapore and the familial connections and social pathways and trade movement via the seas up and down these coastlines are arguably ageless in the scheme of things. Sea State entwines itself within these broader political and cultural relations. Lim’s is not however the only contemporary geographic conception of place for Singapore. Another contrast for example is Singaporean/Malaysian film-maker Sherman Ong’s recent projects, where he imagines the possibility that some day Singapore and Malaysia will become one again. Many would see this though as a rather forlorn possibility.

Charles Lim, Sea State, Singapore Pavilion, 56th International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale 2015, Italy, 9 May – 22 November 2015.