The mind is a muscle: Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Trio A’

In April 2013 a workshop and showing of Yvonne Rainer’s iconic performance piece, Trio A, will be held in Melbourne, Perth and Sydney. I plan to participate in the four-day workshop to be hosted by the VCA.

I was introduced to Trio A via YouTube a few years ago. I had spent the summer in Europe, house-sitting a friend’s apartment and visiting with lots of artists. I was struck by just how strongly choreography and the relationship between object and the moving body had returned to the centre of many young artists’ practices.

Interestingly, my friend, who is a senior artist actively interested in the world and how people are thinking and making, had a new addition to his already extensive book collection—dance. I spent an indulgent month reading my way through a rich collection of catalogues, anthologies and monographs on the likes of Trisha Brown, William Forsythe, Pina Bausch and, of course, Yvonne Rainer. It was Brown’s and Rainer’s works in particular that engaged me: Brown’s relationship to the visual translation of dance, authorship and the authentic revival of works, and Rainer’s tough paring back of dance’s theatre, her focus on the objective presence of the body and its movement, the stringent nature of her No manifesto (1965), and her revision of the relationship to audience.

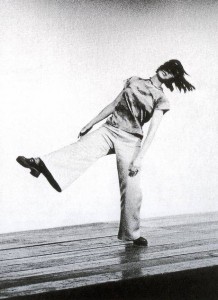

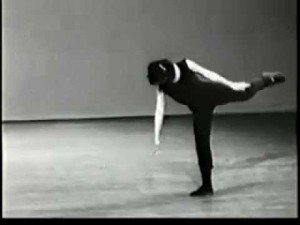

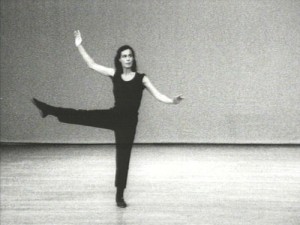

Trio A is a significant work for any artist working with movement. A short work, originally five minutes long, it is a task-oriented performance; a sequence of single movements, one following the other fluidly but without repetition. The piece is executed without regard for the audience. It has been performed in both theatre and gallery environments and adapted and interpreted by dancers and non-dancers alike. Rainer has in fact titled the work under a number of iterations that have allowed her to include film, written and spoken word in its presentation (for example, Trio A geriatric, where Rainer verbalises those actions she can no longer physically perform), and be performed forwards, backwards, in cycles and by others.

A few months ago I read an article (October, no. 140, 2012) by an American scholar, Julia Bryan-Wilson, who has written extensively on Trio A. The article detailed her accidental participation in a Trio A workshop held at the University of California in 2008 and the challenge of relating to the work in a physical rather than cerebral manner. Her article struck a chord with me. I realised I am excited about becoming part of the Trio A alumni yet terrified of being an actual participant. I’ve become so used to relying on my brain that I’m anxious about relying on my body. Perhaps it is that reduction that is at the essence of Rainer’s piece: that space where the mind becomes just another muscle in the body.

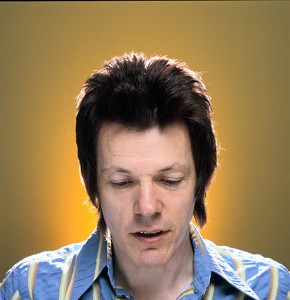

Yvonne Rainer, Trio A, 1978, video, 10:30 minutes.